Sunday, January 31, 2010

303. Aftermath 18: Australia and New Guinea

Before offering my "solution," it's important to remind everyone that the word "solution" is surrounded by quotes, which should probably be in boldface. As I've stressed many times, what I'm doing here is exploring various hypotheses, and not insisting that I've come upon some absolute truth which only needs to be demonstrated to be accepted. There is and always has been tremendous resistance to speculation in the academic world, so it's handy that I am no longer a part of that world and dependent on its power brokers (phew!). But there are those, and not only the academics, who will never forgive one for having ideas and presenting them seriously, as though they might actually be worth something, and so there are those who will never accept that I'm sincere when I say I'm not really in love with my ideas, but only interested in getting them out there so I, and others, can take a good look.

There is, in my opinion, real value in presenting a coherent, consistent hypothesis, based as much as possible on reliable (though certainly not foolproof) evidence, even if it turns out to be wrong. Because even if wrong, such thinking can help to focus all interested parties on the problem at hand, and challenge them to come up with something better.

There will, in any case, probably never be a definitive solution to the problem I've posed for myself in this series, because there are too many things about both Australia and New Guinea that may never be fully known or understood and there is too much room for doubt and endless argument in this respect, and in almost every aspect of the problem, from genetics, to archaeology, to the significance of Dingos and Singing Dogs.

So now, without further ado, here's what I think might have happened, and why. My scenario isn't all that different from the one developed by Birdsell -- in some respects simpler and in others more complex. The numbers in brackets refer to specific, numbered clues, as offered in Posts 298 - 302:

1. Early entry into Sahul by island hopping from Sunda, in the wake of the Out of Africa migration. The earliest immigrants would have been a small band of HMP (Hypothetical Migrant Population) descendants, both male and female, who would have retained an African morphology and an African culture and value system (or, more specifically, some variant of the Hypothetical Migrant Culture -- HMC -- I described in Post 253 et seq.). For example, they would have been singing and playing in some version of P/B style and the women would probably have been assembling beehive huts, very much like those of today's African Pygmies and Bushmen. Since it's possible that HMP were in fact Pygmies, we might want, at least provisionally, to think of the Sahul immigrants as "Negritos." They may well have resembled Negritos, even if some of them may, by that time, have grown to "normal" height (what is normal, anyhow?). The best evidence for their Negrito status would be the "gracile" character of the Mungo Lake fossils, as described by Birdsell. These early immigrants would not have been seriously affected by the population bottleneck(s) I've associated with the Toba eruption (or some equally devastating event), as they would presumably have been living far enough to the east of India at the time to be unaffected or only minimally affected, and therefore would have retained their original African characteristics to at least some significant degree. If this were not the case, then it would be difficult to explain the survival of P/B-related musical traditions, both vocal and instrumental, among so many Melanesian groups today, as well as the Negrito morphology of certain groups in highland New Guinea, such as the Eipo, as well as the few surviving Australian Pygmies studied by Birdsell [see clues 1-3, & 8 ]. There are also remarkable wood working and mask making traditions now found in Melanesia that bear a striking resemblance in many ways to those of Africa.

2. This original immigrant band, Negrito or quasi-Negrito, would have rapidly expanded throughout the entirety of Sahul, from what is now New Guinea to what is now Australia and also Tasmania, which would have been attached to the mainland by a land bridge. [8] They may well have still been speaking the original HMC language, which would, in all likelihood, have been a tone language -- since almost all African languages are tonal.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

302. Aftermath 17: Australia and New Guinea

Three more clues, and then I'll be ready to "solve" the case.

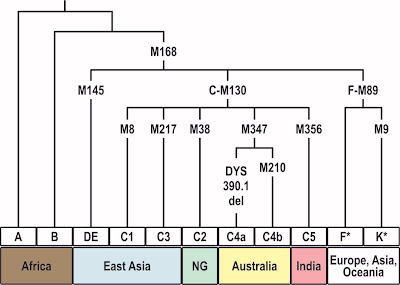

14. Thanks to German Dziebel, I've been made aware of yet another paper on the Australian genetic picture, Revealing the prehistoric settlement of Australia by Y chromosome and mtDNA analysis, 2007, by Georgi Hudjashov et al. Since the Indian-Australian connection has been a matter of fierce debate for many years, it's not surprising that these authors contest previously published findings that appeared to support such a connection (see clues no. 5, 6, 8 & 9 in Posts 299 and 300, below). In other respects, however, their findings are similar: The relevant Y phylogeny is summarized in Figure 3: As you can see, the new Y marker, labeled M347, gives rise to the two Australian subclades, C4a and C4b, which can indeed be distinguished from C5, found only in India. Comparing the above with the map we've already seen, as published in Redd et al, 2002 (see Post 299, below), I'm not sure I see a discrepancy:

What Redd et al were pointing to is the distribution of C*, i.e., the clade on which all the other C haplogroups are rooted. As is evident from Hudjashov's Figure 3, this root clade, based on the mutation marker M130, is found in East Asia, New Guinea, Australia and India, exactly where C* is found in the Redd map, if we pay attention to the red pie chart segments. So what Redd et al. were demonstrating, as far as I can see, is the continuity of the C macrohaplogroup as it appears to have migrated from India, and across SE Asia, to Australia and Melanesia (where in each place, as stands to reason, it would have given birth to subclades). And a big part of the problem is the question of when this migration might have taken place. For Hudjashov et al., this must have happened at the same time as the original Out of Africa migration, ca 70,000 ya. But the coalescence figures Redd et al. came up with suggest an origin for C dating from much later, roughly 8,000 ya.

12. The legendary Australian dog known as the "Dingo" is thought to be a relatively recent arrival, judging from fossil remains. According to Wikipedia, the oldest dingo fossils date back roughly 5,000 to 5,500 years in Thailand and Vietnam. Their history in Australia is more recent:

Today, the most common theory is that the dingo arrived in Australia about 4,000 years ago, due to the fact that the oldest known fossils of dingoes were estimated to be about 3,500 years old and were found in various places in Australia, which indicates a rapid colonization. Findings are absent from Tasmania, which was separated from the main Australian landmass around 12,000 years ago due to a rise in sea level. Therefore, archeological data indicates an arrival between 3,500 to a maximum of 12,000 years ago. To reach Australia from Asia, there would have been at least 50 km of open sea to be crossed, even at the lowest sea level. Since there is no known case of a big land animal who made such a journey by itself, it is most likely that the ancestors of modern dingoes were brought to Australia on boats by Asian seafarers (my emphasis).

Another species, considered by some to be closely related to the Dingo is the New Guinea "singing dog," thought to have been genetically isolated for ca 6,000 years.

13. Associated with the introduction of the Dingo, were some other important changes:

Archaeological evidence suggests that from around 5000 BC there were substantial changes in Indigenous Australian population density, settlement pattern and technology. About 4000 years ago the dingo was introduced to Australia from Asia, and this seems to have increased the efficiency of Indigenous Australian hunting. At about the same time a new range of small, sharp-edged stone tools came into use. The population increased and expanded to occupy new areas. There was also a large increase in the distance that objects moved along trade routes.

It is not known if this new technology arrived with a wave of immigrants who brought the dingo with them, or if it arose through technical innovation in Australia (WorldTimelines).

14. Thanks to German Dziebel, I've been made aware of yet another paper on the Australian genetic picture, Revealing the prehistoric settlement of Australia by Y chromosome and mtDNA analysis, 2007, by Georgi Hudjashov et al. Since the Indian-Australian connection has been a matter of fierce debate for many years, it's not surprising that these authors contest previously published findings that appeared to support such a connection (see clues no. 5, 6, 8 & 9 in Posts 299 and 300, below). In other respects, however, their findings are similar:

These results indicate that Australians and New Guineans are ultimately descended from the same African emigrant group 50–70,000 years ago, as all other Eurasians. In other words, these data provide further evidence that local H. erectus or archaic Homo sapiens populations did not contribute to the modern aboriginal Australian gene pool, nor did Australians and New Guineans derive from a hypothetical second migration out of Africa (38), nor is there any suggestion of a specific relationship with India (8727 -- my emphasis).

The most convincing evidence for an original settlement of both New Guinea and Australia by the same group of Out of Africa migrants, ca 50,000 - 70,000 ya, comes from the female (mtDNA) side, as is the case with all the other studies. They argue for a similarly long-term connection on the male (Y chromosome) side as well, and no connection whatsoever with India. Yet, at the same time, with one possible exception, all indications are that New Guinea and Australia have had separate histories ever since the initial arrival in Sahul:

Apart from this potential signal of secondary migration into

Australia, there seem to be no further lineages either on the

Australian Y or mtDNA tree that would provide clear evidence

for extensive genetic contact since the first settlement, except

possibly for a P3 sublineage shared between Australia and NG

(Fig. 2). Thus, Australia appears to have been largely isolated

since initial settlement, in agreement with one interpretation of

the fossil record (10, 11). In particular, there are no lineages

exclusively shared between Australia and India that might have

indicated common ancestry as originally proposed by Huxley (9).

Indeed, we have identified a new Y marker M347 (Fig. 3), which

distinguishes all Australian C types from Indian or other Asian

C types and adds weight to the rejection of the Huxley hypothesis.

What Redd et al were pointing to is the distribution of C*, i.e., the clade on which all the other C haplogroups are rooted. As is evident from Hudjashov's Figure 3, this root clade, based on the mutation marker M130, is found in East Asia, New Guinea, Australia and India, exactly where C* is found in the Redd map, if we pay attention to the red pie chart segments. So what Redd et al. were demonstrating, as far as I can see, is the continuity of the C macrohaplogroup as it appears to have migrated from India, and across SE Asia, to Australia and Melanesia (where in each place, as stands to reason, it would have given birth to subclades). And a big part of the problem is the question of when this migration might have taken place. For Hudjashov et al., this must have happened at the same time as the original Out of Africa migration, ca 70,000 ya. But the coalescence figures Redd et al. came up with suggest an origin for C dating from much later, roughly 8,000 ya.

While Hudjashov et al provide a table of mtDNA age estimates, dating as far back as 65,900 +- 13,200 (for haplogroup P4), they don't provide anything similar for Y, nor do I see, anywhere in their paper, any estimate for the emergence of the all important M130 and M347 mutations. Without such an estimate, one wonders how it was possible for them to conclude that the female and male lines both date to the original Out of Africa migration, and thus, contrary to Redd et al, have the same histories. Nor is it easy to understand, if they indeed did have the same histories, and there was no subsequent immigration event, how the two populations, once united on Sahul, but now on separate islands, are now so different in so many ways, both morphologically and culturally.

301. Aftermath 16: Australia and New Guinea

11. An especially interesting paper on the female lineages of Australia and New Guinea was presented by Max Ingman and Ulf Gyllensten in a 2003 publication, Mitochondrial Genome Variation and Evolutionary History of Australian and New Guinean Aborigines. While most such studies have traditionally concentrated on the "neutral," non-coding segment of the mtDNA "D-loop," this segment "is characterized by a high frequency of homoplasy" (i.e., it is subject to back mutations that make it more difficult to construct an accurate phylogenetic tree) not found in the coding region. They decided, therefore, to produce

I'll be discussing some of the themes raised above in my next post, when I finally try to put all the various bits and pieces of evidence together into some kind of theory.

a tree reconstructed using just the coding region sequences (Fig. 2). Although the topologies of the two trees were essentially the same, the tree of sequences with the D-loop removed showed generally higher bootstrap values. For this reason, in studying the phylogenetic relationships among the mitochondrial lineages, we focused solely on the coding region (1601).

Here is the tree they came up with (click to enlarge):

Since they weren't using the usual D-loop markers, they decided against the usual mtDNA haplogroup nomenclature, based on L, M, N, etc. Their results are essentially equivalent, however:

Since they weren't using the usual D-loop markers, they decided against the usual mtDNA haplogroup nomenclature, based on L, M, N, etc. Their results are essentially equivalent, however:

Since they weren't using the usual D-loop markers, they decided against the usual mtDNA haplogroup nomenclature, based on L, M, N, etc. Their results are essentially equivalent, however:

Since they weren't using the usual D-loop markers, they decided against the usual mtDNA haplogroup nomenclature, based on L, M, N, etc. Their results are essentially equivalent, however:Branch 1 and branch 2 are delineated by the nucleotide positions 8701, 9540, 10398, 10400, 10873, 14783, 15043, and 15301 relative to the Cambridge reference sequence (CRS; Anderson et al. 1981), consistent with what are sometimes referred to as haplogroups N (branch 1) and M (branch 2) (1601).

Those clades containing sequences from New Guinea are blocked out in green. Interestingly, there are only four basic types: 2a, a mix of highland and coastal New Guinea, plus a Nasioi speaker from Bougainville, in the Solomons -- this clade coalesces to 45,000 +- 9,000 years ago, "calculated from the deepest genetic split," suggesting that the coastal sequences are not of Austronesian descent, since this population is a relatively recent arrival; 1c and 1d, Australia and highland New Guinea; 1b, almost exclusively highland New Guinea, coalescing at 36,000 +- 8,000 ya; and 1a, coastal New Guinea and Western Polynesia, coalescing at 11,000 +- 4,000 ya, suggesting a relatively recent Austronesian origin for all. Note the many exclusively Australian clades (not marked).

An ongoing theme in the genetic story from this part of the world is a surprising male-female difference, and Australia is no exception:

Our analysis shows a striking difference between the genetic history of females and the reported history of males in the Australian Aboriginal population. As noted previously, the mitochondrial diversity in Australia is relatively high. The pattern seen in the Y-chromosome is different in that an Australia-specific haplotype (DYS390.1del/RPS4Y711T) is found in about 50% of males in Australia (Kayser et al. 2001; Redd et al. 2002). . . Kayser et al. (2001) proposed that the high frequency of a unique haplotype in Australia is the result of a population expansion that started from a few hundred individuals. In this case, the predominance of a unique Y-chromosome haplotype in Australia would be the result of a founder effect. However, there does not appear to be a corresponding loss of genetic diversity resulting from a bottleneck seen among mitochondrial lineages (1604 -- my emphasis).

In other words, the major discrepancy between Australian Y and mtDNA diversity suggests a bottleneck in the former, yet none in the latter, which seems puzzling -- unless males and females have a very different history on this continent.

Here's a summary of the author's conclusions, with some italicizing by me:

Archaeological evidence indicates that humans were present in New Guinea at least 40,000 years ago (Groube et al. 1986), at which time it was still joined with Australia. Our data show that some Australian sequences do share a closer ancestry with some New Guinean sequences than they do with other sequences on branch 1. In addition, . . . New Guinean and Australian sequences are more closely related to each other than either are to the Asian sequences. This may suggest that Australia and New Guinea were colonized jointly or that, if not, these populations have admixed since colonization. . . Our mitochondrial data imply that some lineages from the populations of Australia and New Guinea have shared a common history since the initial colonization of Sahul. . . .The lack of a common Y-chromosome haplotype found both in Australia and in theNew Guinea highlands (or in any other Melanesian population) argues against the concept that the New Guinean and Australian populations are derived from the same migration event (Kayser et al. 2001). However, the Australia-specific Y chromosome haplotype could have arisen after the colonization of Sahul and therefore is absent in other populations.Our mitochondrial data show no clear similarity between Australian Aborigines and the three southern Indian sequences examined, although a detailed examination of this hypothesis would require the analysis of additional individuals from the Indian Subcontinent. Nevertheless, mitochondrial DNA only provides information on the genetic history of females, and given the contrast between the mitochondrial DNA and the Y chromosome patterns, it appears that additional studies of autosomal loci are also necessary to obtain a balanced view of the evolutionary history of the peoples in this region.

I'll be discussing some of the themes raised above in my next post, when I finally try to put all the various bits and pieces of evidence together into some kind of theory.

Friday, January 29, 2010

300. Aftermath 15: Australia and New Guinea

( . . . continued from previous post.)

As I've already noted, Birdsell's research confirmed the almost mythic existence of heavily marginalized Pygmies in Australia, which made it logical for him to conclude they were most likely descended from the "Barrineans." For Birdsell, the Tasmanians, who may have had a similar morphology, judging from various remains, had also been Negritos, and therefore must also have been descended from the earliest immigrants. (There are other reports, not necessarily contradictory, suggesting that the Tasmanians resembled Melanesians more than other Australians.) Which might lead one to infer that Tasmania, like many islands, may have functioned as a refuge area. This is of course based on very speculative thinking, since little is actually known about the Tasmanian people and their culture -- and Birdsell's "tri-hybrid" theory has been disputed and is no longer a part of mainstream anthropology (possibly due to "political correctness" concerns, as it flew in the face of a very popular movement promoting the idea that all aboriginals were descended from the original inhabitants).

9. In 1999, Alan Redd and Mark Stoneking published one of the pioneering studies of Australian/Papuan genetics, Peopling of Sahul: mtDNA Variation in Aboriginal Australian and Papua New Guinean Populations. While their research has since been superseded (though not necessarily contradicted) by more complete studies, even at this early stage the authors found significant links between Australia and India, though little evidence linking Australia with New Guinea:

Thus, it appears, from the intermatch distributions, that the Aboriginal Australian and southern Indian populations derive from the same ancestral population, whereas the highland PNG [Papua New Guinea] population derives from a completely different ancestral population.

As with the more recent study of Y chromosome evidence by Redd et al., as reported in the previous post, they found the India-Australia association to be relatively recent:

Furthermore, the net separation between Aboriginal Australian populations and southern Indian populations appears to be much more recent than the separation between Aboriginal Australian populations and PNG highland populations. The precision of the estimated divergence times should be considered somewhat cautiously, since these estimates are associated with large uncertainties. However, the patterns are consistent with a separate origin (or ancient separation) for PNG highlanders and Australian Aboriginals and with recent genetic affinities between southern Indian populations and Aboriginal Australian populations.Interestingly enough, they take special note of Birdsell's supposedly discredited theory:

These findings are somewhat consistent with Birdsell’s trihybrid model for the peopling of Sahul . . . Birdsell hypothesized that Oceanic “Negritos” first populated Sahul, but that two later migrations replaced most of them in Australia but not in the Cairns area of northeast Queensland or in Tasmania and New Guinea. According to this model, the second migration of populations, with affinities to the Ainu of Japan, dispersed throughout Australia, whereas the third migration of populations, with affinities to tribal populations of India, entered northern Australia around the Gulf of Carpentaria. The gene tree in the present study shows that the PNG3 cluster shares sites with African sequences, a finding that may be consistent with Birdsell’s first-migration hypothesis. Our results also suggest that there may have been a migration(s) from an Indian source that reached Australia but not PNG. However, our results do not support two distinct source populations for the subsequent peopling of Australia, because Aboriginal Australian populations cluster together with southern Indian populations. . .Their summary is especially relevant for our purposes, as it highlights the connection they found between highland Papua New Guinea and Africa:

To summarize, our data indicate that the PNG highlanders contain distinct and divergent mtDNA, with evidence of ancient African ties, that were rare or absent in Aboriginal Australians and suggest a possible recent connection between Aboriginal Australian populations and populations from the Indian subcontinent (824 -- my emphases).10. In addition to the Tasmanians, another very interesting population can be found in the islands of the Torres Straits, separating the northernmost Cape York Peninsula region of Australia from New Guinea:

From Wikipedia:

The islands' indigenous inhabitants are the Torres Strait Islanders, Melanesian peoples related to the Papuans of adjoining New Guinea. The various Torres Strait Islander communities have a distinct culture and long-standing history with the islands and nearby coastlines. Their maritime-based trade and interactions with the Papuans to the north and the Australian Aboriginal communities have maintained a steady cultural diffusion between the three societal groups, dating back thousands of years at least (my emphasis).It seems surprising to see a people with a fundamentally Melanesian morphology and culture living in such close proximity to Australian aborigines, yet maintaining, over thousands of years, an almost total independence of outlook. This is reflected in their musical culture as well, as their singing tends to be open-throated and polyphonic, in striking contrast to the tense voiced solos and unison choruses of their close neighbors to the south. Once again, as with Tasmania, we see the possibility that the islands of Torres Strait could have served as a refuge area.

Thursday, January 28, 2010

299. Aftermath 14: Australia and New Guinea

( . . . continued from previous post.)

Figure 2 from this paper represents the worldwide distribution of Y haplogroup (hg) C:

The segments in red represent subhaplogroup C* (or C root), which was the focus of this study. Remarkably, one can trace the migration of C* from its first appearances, in south India and Sri Lanka (SRL), through Southeast Asia (SEA) and East Indonesia (EIN) to the Australia Aboriginal People (AAP), where it is present in fully half the male population sampled.

Note especially the leaps with both legs simultaneously and the upraised arms toward the beginning of the clip, very similar to what we see in the Chenchu segment.

Stephen Oppenheimer writes as follows of the Chenchu, in connection with the M2 haplogroup and its possible relation to the Toba eruption:

5. In an article titled Gene Flow from the Indian Subcontinent

to Australia: Evidence from the Y Chromosome, by Alan Redd et al., 2002, the authors present "strong evidence for an influx of Y chromosomes from the Indian subcontinent to Australia . . . " (the Y chromosome is found only in males and can represent only male lineages):

to Australia: Evidence from the Y Chromosome, by Alan Redd et al., 2002, the authors present "strong evidence for an influx of Y chromosomes from the Indian subcontinent to Australia . . . " (the Y chromosome is found only in males and can represent only male lineages):

In sum, we found that 50% of the Y chromosomes sampled from aboriginal Australians share common ancestry with a set of Y chromosomes that represent less than 2% of the sampled Indian subcontinent paternal gene pool. The similarity among C* chromosomes is unlikely to have been caused by chance convergence because we genotyped ten independent STRs. The observed pattern is not specific to central Australians, since our sample also included individuals from the Great Sandy Desert and from Western Australia, and our estimate of the frequency of C* chromosomes agrees remarkably well with other studies of greater numbers of aboriginal Australian Y chromosomes in Arnhem Land, the Great Sandy Desert, the Kimberleys, and the Northern Territory. (676 -- my emphasis).

While only 2% of the male gene pool for India might seem insignificant, it's important to remember that the C* haplogroup is found only among certain tribal peoples in south India and Sri Lanka (where we find many australoid types today). It would be very strange indeed if the figure were much higher than 2%, since Australian aborigines bear little physical or cultural resemblance to East Indians generally. However, the figure shoots up to 50% in Australia, a remarkably strong representation. While the Y chromosome represents male lineages only, the authors refer to an earlier study in which "affinities between Australian Aboriginal People and mainland southern Indians were suggested based on maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA" (673).

Figure 2 from this paper represents the worldwide distribution of Y haplogroup (hg) C:

The segments in red represent subhaplogroup C* (or C root), which was the focus of this study. Remarkably, one can trace the migration of C* from its first appearances, in south India and Sri Lanka (SRL), through Southeast Asia (SEA) and East Indonesia (EIN) to the Australia Aboriginal People (AAP), where it is present in fully half the male population sampled.

While these results are indeed impressive, the connection they found may be relatively recent. According to their estimates, C* dates only to the mid-Holocene, roughly 8,000 years ago, which places this particular migration well past both the Out of Africa exodus and the Toba eruption. Since the paper dates from 2002, and much has since been learned about the distribution of the C haplogroup, it's possible that these results may have been superseded, but if so I'm not aware of it. If anyone reading here has more up-to-date information on the distribution of C in India and/or Australia, I'd like very much to see it.

6. A much more recent paper, Reconstructing Indian-Australian phylogenetic link, by Satish Kumar et al., published in July 2009, sees a connection on the female line, as represented by mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA):

Background: An early dispersal of biologically and behaviorally modern humans from their African origins to Australia, by at least 45 thousand years via southern Asia has been suggested by studies based on morphology, archaeology and genetics. However, mtDNA lineages sampled so far from south Asia, eastern Asia and Australasia show non-overlapping distributions of haplogroups within pan Eurasian M and N macrohaplogroups. Likewise, support from the archaeology is still ambiguous.Results: In our completely sequenced 966-mitochondrial genomes from 26 relic tribes of India, we have identified seven genomes, which share two synonymous polymorphisms with the M42 haplogroup, which is specific to Australian Aborigines.Conclusion: Our results showing a shared mtDNA lineage between Indians and Australian Aborigines provides direct genetic evidence of an early colonization of Australia through south Asia, following the "southern route".

Moreover, "The divergence of the Indian and Australian M42 coding region sequences suggests an early colonization of Australia, ~60 to 50 ky BP, quite in agreement with archaeological evidences." In this case, the coalescence dates are within range of both Out of Africa and Toba.

However, the investigators were able to match only 7 individuals from India with 6 from Australia, a far less convincing result than the 50% representation for C* throughout Australia generally, as found in the Y chromosome study.

7. It would be much easier to argue for an Indian-Australian cultural connection if there were any distinctive musical similarities between Tribal India and Aboriginal Australia, but so far I haven't found any. (Unfortunately, the music of Tribal India has not been studied or even recorded as thoroughly as that of other indigenous populations, so I may have missed something -- though I doubt it.) However, I recently came across a remarkable Youtube clip of dancing among the Chenchu hunter-gatherers of South India that strongly resembles Australian Aboriginal dancing:

While the very opening contains some interesting moves, the most remarkable similarities with Australia can be found at the 1:30 and 2:30 marks. (Ignore the pretentious commentary.)

Here's a Youtube clip of Australian Aboriginal dancing for comparison:

Stephen Oppenheimer writes as follows of the Chenchu, in connection with the M2 haplogroup and its possible relation to the Toba eruption:

The eldest of [the] many daughters [of haplogroup M] in India, M2, even dates to 73,000 years ago. Although the date for the M2 expansion is not precise, it might reflect a local recovery of the population after the extinction that followed the eruption of Toba 74,000 years ago. M2 is strongly represented in the Chenchu hunter-gatherer Australoid tribal populations of Andhra Pradesh, who have their own unique local M2 variants as well as having common ancestors with M2 types found in the rest of India. Overall, these are strong reasons for placing M’s birth in India rather than further west or even in Africa.(to be continued . . . )

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

298. Aftermath 13: Australia and New Guinea

In addition to the problem summarized at the end of the last post, concerning the many differences between the populations of Australia and New Guinea, there is another problem with Australia in itself, a problem I addressed in my paper, Echoes of Our Forgotten Ancestors:

3. There are also Pygmies in New Guinea, e.g. the Eipo people, whose males average 146 centimeters in height (or 4.79 feet). The music of the Eipo bears the "African signature," in the form of vocal hocket, with some instances of yodel.

4. Certain tribal peoples in southern India have been characterized as having a relatively "robust," "Australoid" morphology, strongly resembling that of the Australian aborigines. For this reason, it has long been thought that there could be a relation between the two groups -- and since the advent of the Out of Africa model, there has been speculation that the Australians might be descended from Africans who developed an "Australoid" physiognomy in India. Some recent genetic studies have claimed to support such a theory, at least in part, though the results may be inconclusive.

(to be continued . . .)

If the original Out-of-Africa group moved uniformly all the way from Africa down the coast of south Asia to the Malay Peninsula and from there down through Indonesia to New Guinea and Australia, as is sometimes claimed, then we musicologists have a problem. While many indigenous groups along the “beachcomber” route sing and play in a manner strongly reminiscent of P/B style, there has to my knowledge never been any instance of such a style found anywhere in Australia. I have never heard of panpipes there either. In fact the musical style of the Australian aborigines is dramatically different from the types of music under discussion thus far.

Considering the importance of Australia as the bearer of the earliest archaeological evidence of modern humans outside of Africa, evidence which so strongly supports the southern route model, the absence of any trace of the "African signature" in any of its native music definitely requires an explanation. If the Out of Africa migrants were singing and playing in some version of P/B style, as I feel sure they were, then what could have happened when they got to Australia that made them lose their musical traditions and develop such different ones? And since we do in fact find many instances of the African signature in New Guinea (and Island Melanesia as well), its absence in Australia is just one more mystery we can add to all the others.*

I would like to propose an explanation that might resolve all or most of the contradictions in one stroke, which again, like so much else I've been discussing on this blog, should be seen as exploratory, speculative and provisional. It may not be the correct solution, or maybe only partly correct, but it can at least help to focus our thinking.

Let's first examine some possibly significant clues:

1. Fossil bones of modern humans have been found near Mungo Lake in Australia, originally dated to ca 60,000 ya, but now thought to be no more than 45,000 years old. "Mungo Man" appears to be the oldest modern human remains to be found outside of Africa. However, the most complete skeleton found "was of a gracile individual, which contrasts with the morphology of modern indigenous Australians." So-called "robust" skeletons of a very different type than Mungo have also been found, but they are much more recent, dating to ca 10,000 ya.

2. There is reason to believe that Pygmies lived in Australia until very recently. This is not the "urban myth" some might think, but was studied and documented by a highly respected anthropologist, Joseph Birdsell:

3. There are also Pygmies in New Guinea, e.g. the Eipo people, whose males average 146 centimeters in height (or 4.79 feet). The music of the Eipo bears the "African signature," in the form of vocal hocket, with some instances of yodel.

4. Certain tribal peoples in southern India have been characterized as having a relatively "robust," "Australoid" morphology, strongly resembling that of the Australian aborigines. For this reason, it has long been thought that there could be a relation between the two groups -- and since the advent of the Out of Africa model, there has been speculation that the Australians might be descended from Africans who developed an "Australoid" physiognomy in India. Some recent genetic studies have claimed to support such a theory, at least in part, though the results may be inconclusive.

(to be continued . . .)

*We could, of course, assume that only a very small group were the first to land on the Australian shore, a group too small, and perhaps also too young, to properly sustain so group-oriented, interactive and complex a practice as P/B; in which case the resulting population bottleneck could have produced a cultural founder effect that could in turn have led to a drastic loss and/or simplification of traditional musical practices. Unfortunately a scenario of that kind, while it might account for the musical anomaly, leaves too many other questions unanswered, especially the question of how and when New Guinea was populated, and why we see no sign of the influence of New Guinea culture (rituals, languages, music, etc.) in Australia despite the fact that the two land masses were joined until only about 10,000 years ago.

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

297. Aftermath 12: Australia and New Guinea

At the time of the early migrations, water levels in the oceans were much lower than they are today, and as a result many of the islands of Island Southeast Asia were linked with the Malaysian mainland to form a single peninsula, called Sunda; and Australia and New Guinea were also linked, to form a single continent, Sahul:

As you can see from the map, the low water levels meant that a sea crossing by island hopping from Sunda to Sahul would not have been too much of a challenge -- especially since, as is now suspected, the Out of Africa migrants had already been doing much of their traveling by boat. Since some of the earliest archaeological evidence of modern human habitation associated with the Out of Africa migration comes from Australia, and since some of the arguably "oldest" populations (based on both their genetic and cultural makeup) now live in New Guinea and Australia, it stands to reason that the Sahul must have been part of the earliest migration along the "southern route."

As you can see from the map, the low water levels meant that a sea crossing by island hopping from Sunda to Sahul would not have been too much of a challenge -- especially since, as is now suspected, the Out of Africa migrants had already been doing much of their traveling by boat. Since some of the earliest archaeological evidence of modern human habitation associated with the Out of Africa migration comes from Australia, and since some of the arguably "oldest" populations (based on both their genetic and cultural makeup) now live in New Guinea and Australia, it stands to reason that the Sahul must have been part of the earliest migration along the "southern route."

But there is a problem. If Sahul were populated by Out of Africa migrants when both New Guinea and Australia were joined into a single landmass, as illustrated in the above map, and both regions had remained relatively isolated from then to now, as has been argued, we would expect the populations that now live in both places to be quite similar, both morphologically and culturally. And we would certainly assume that they'd be closely related genetically as well. This, however, is not the case. There are in fact many differences between the peoples of New Guinea and Australia:

1. New Guinea is far more complex and heterogeneous both morphologically and culturally, with many different groups living in fairly close proximity to one another, and constantly at war with one another, which tended to isolate the various groups in place, possibly for tens of thousands of years. Australia would appear to be much more homogeneous in both respects, with almost all aborigines sharing distinctively "Australoid" features and having many cultural traditions in common. It's also worth noting that the Tasmanians, who are now extinct, are thought to have resembled Melanesians more than other Australians; and that there is very good evidence of the existence of Negrito peoples in some parts of the continent, as recently as the early 20th century.

2. Possibly because of their prolonged isolation from one another, due to warfare, there are far more different languages and language families in New Guinea than anywhere else on Earth. By comparison, most of Australia is dominated by a single language family, called Pama-Nyungan. Wikipedia lists 15 other language families for Australia, but these are all crowded into a relatively small area in the north, in the region which is, significantly, closest to New Guinea.

3. Musically, New Guinea is a relatively heterogeneous island, with several different vocal styles and many different types of instruments. In several cases, we find the African signature, in the form of P/B-related vocal styles and also instances of instrumental hocket, especially with wind ensembles of pipes, panpipes, trumpets and flutes, unmistakably African in origin. Among other groups, we find various types of unison singing, sometimes similar to what we find in Australia. And in still other cases, we hear relatively simple polyphonic vocalizing not unlike Western Polynesian singing. Australia, on the other hand, is among the most musically homogeneous regions in the world, with a characteristically tense, nasal vocal style, either solo or unison, accompanied by sticks or boomerangs beaten together to produce relatively simple one-beat rhythms or simple variants of the one-beat pattern. This type of singing, characterized, as is North American Indian singing, by the iteration of a single note at the beginnings and endings of phrases, pervades the entire continent, so far as I've been able to determine, though occasionally one hears something more complex, with traces of polyphony and even interlock. The only important musical instrument is the Didgeridoo, which was traditionally found only in the north and is thought to be a relatively recent innovation. The above descriptions are deceptive, however, as Australian singing and Didgeridoo playing are among the most sophisticated musical art forms in the entire world. The texts that go with these songs are also remarkable examples of highly sophisticated, allusive and complex poetry.

So we are faced with the very interesting question of why these two populations, despite certain intriguing similarities, are so different in so many ways.

(to be continued . . . )

Sunday, January 24, 2010

296. Aftermath 11: The Later Migrations

The scenario I've presented in the last few posts is based on an attempt to co-ordinate Stephen Oppenheimer's interpretation of the genetic evidence, including his Toba bottleneck theory, with what I've learned of the musical evidence, and what I am learning about the overall ethnographic picture. I call it an exploration because as I write I am considering other possibilities, exploring the various options for evaluating and interpreting each, and measuring all this against the original hypothesis.

So what has been learned from the exploration so far, and what other options might we consider as we attempt to relate various possibilities to the evidence? And I suppose the answer would be that the possibilities that emerge depend to a large extent on the sort of problems that come to mind. If you see no problem with a straightforward functionalist/diffusionist explanation for the cultural, morphological and genetic similarities and differences we now see in the world around us, and are content to accept independent invention as the best explanation for all the many widespread but isolated similarities not easily attributable to diffusion, then there is no problem with the most straightforward Out of Africa scenario: a small group of humans migrated from Africa to Asia; their descendants expanded along the southern coast of that continent, settling at first in India, where they quickly expanded throughout all of South Asia, with some continuing on to Southeast Asia and eventually migrating from there to East Asia, Siberia and Central Asia, with one or more of the Western colonies branching out to Europe at some point.

The many differences we now see in the world around us would therefore be due to the various adaptations people made to the different environments in which they found themselves; and the similarities would be due to the ways in which certain cultural elements diffused over time from one group to another -- or else to the workings of "convergent evolution," where by virtue of some inborn, universal process that can't really be explained different groups in different places find themselves evolving in a similar direction.

This is one way of thinking about the Out of Africa model, and about anthropology generally, and if one is not overly critical it might seem the most likely and/or reasonable scenario. Whatever problems it might encounter can be attributed to our lack of detailed information regarding exactly how certain features get diffused from one group to another to facilitate change, or how certain practices can be explained as cost-effective adaptations to environmental pressures, or how various encounters and interactions among various neighboring groups can produce, via some sort of genetic and/or cultural "drift," large geographical regions that differ from one another, morphologically, genetically and culturally. This all fits quite nicely with anthropology as currently practiced, where almost all the effort is concentrated on sifting through the myriad details required to explain all the many mini-problems that will invariably emerge from such a vaguely defined model.

This very "reasonable" approach to human evolution breaks down when we see certain problems that become evident only when we do something very few anthropologists of today seem willing to do: carefully and critically examine the patterns that emerge when we consider the large-scale distribution of cultural practices worldwide. The current mainstream approach is a bit like the old Ptolemaic theory of the universe, where the Earth was at the center and all the heavenly bodies revolved around it according to "epicycles" that could only be determined through painstaking and detailed observation and calculation, not at all unlike the laborious efforts of all the armies of anthropologists, archaeologists, paleontologists, etc. seeking to make sense of the human world by either counting and classifying every single stone, bone and sherd or interviewing every "native" in sight.

What convinced me that there is something very wrong with this picture was my discovery, thanks to Alan Lomax, of the remarkably consistent large-scale patterns we become aware of as we systematically study the various musical practices of traditional cultures on a worldwide basis. And once that door is opened, then a magnificent socio-cultural vista becomes discernible, rich with many other possibilities -- and problems.

So. To respond to some comments posted here, accusing me of failing to consider alternatives to the hypothesis I've been exploring, my answer is that I have in fact considered the alternative described above, which is in fact the mainstream interpretation of human evolution generally accepted, in one form or other, by almost all anthropologists, and have been forced to reject it, precisely because it fails to account for certain key pieces of evidence that become apparent only when considering the big picture.

What does this big picture tell us? The answers to that question can be found all over this blog, so there is no need for me to go into all that all over again. But the chief thing on my mind when considering the problem of the later migrations, the key piece of evidence that hits me especially hard as a musicologist, has to do with the distribution of a particular, highly distinctive, musical style, and its various substyles -- namely, what Lomax once called "elaborate style," a type of solo singing characterized by elaborate embellishment; wordiness; complex, "through-composed" forms, often built around various combinations of "mosaic" elements; narrow intervals; frequent use of microtones and other types of vocal nuance; improvisation; tense, constricted vocal timbre; precise enunciation of consonants; accompanied by instruments playing variants of the same melodic line in a manner technically called "heterophony." This is a style of music-making commonly found throughout Asia, from the Middle East (including North Africa) to India to East Asia, Southeast Asia, Island Southeast Asia, and, in a somewhat less extreme form, in Central Asia as well.

As I see it, first of all, it's all but impossible to account for such a style on the basis of a gradual evolution from P/B or any other typically African type of music making. So, unless we are willing to accept the multiregional model, which goes against just about all the genetic evidence, we are, as far as I can see, forced to accept that this is a style that could only have emerged as the result of some sudden, and indeed radical, change. And secondly, the extremely wide distribution of the style, not only among the "high cultures" of Asia and North Africa, but also in so much of the "folk" and even indigenous music as well, combined with the almost total absence of any form of vocal polyphony anywhere in the whole of Asia (with the exception of the many widely scattered, marginalized and isolated groups I've already mentioned), we are drawn almost inevitably to the conclusion that both the absence of polyphony and the presence of this totally different musical style must be due to some dramatic event that could have had such widespread consequences only if it had occurred somewhere in Asia, at some very early period of human history.

[Added 9:54 PM: Sorry, but I forgot to consider Asiatic Russia, which does indeed have some remarkable polyphonic vocal traditions, though Russian folk polyphony seems more closely related to somewhat similar traditions in Europe and also Georgia (which is itself on the cusp between Europe and Asia) than to anything elsewhere in Asia. While true Russian folk polyphony is widespread, both in Europe and Asia, it appears to also be a marginalized survival, largely confined to forest or highland refuge areas.]

So what I am exploring is the various pieces of evidence that have emerged over the last 20 years or so, largely from the field of genetics, to see whether that evidence is consistent with what we see in the musical evidence. And so far I have to say that at least some of this evidence does support the hypothesis I've been considering. But certainly not all. And there are still some very interesting problems that remain.

Saturday, January 23, 2010

295. Aftermath 10: The Later Migrations

Starting from where I left off in Post 293, I'll continue with item 4 of my Later Migrations scenario:

4. ca 73,000 - 70,000 ya: Assuming a bottleneck or bottlenecks after Toba, or some other disaster in the same region, we can't be sure how many such bottlenecks would have occurred. It's even conceivable that only one group might have survived in the general area, either in India itself or to the east. Or possibly there were many groups with at least a few survivors, and thus many different founder effects. It's also very difficult if not impossible to correlate such founder effects with the genetic evidence. A major disaster at that time may well have produced one or many population bottlenecks by destroying human life en masse, but we have no reason to assume it would have produced even a single mutation. So it would be a mistake to read a separate founder effect into each different branch of M, N, or R.

Following Oppenheimer, I will at this point explore the possibility he raises, that the eruption would have completely destroyed all humans caught within range of the thickest fallout, which means that the tribal (and many of the lower caste) populations we now see in India originated either west or east of the subcontinent, from where various scenarios of repopulation would have occurred. If the pocket we identified in the northwest Punjab-Kashmir region survived, then west India might have been repopulated from there. As for repopulation from the east, any groups living just east of India during the Toba blast would almost certainly have suffered serious bottlenecks and may well have lost at least some of their original African traditions.

This could explain the absence of significant P/B characteristics in their music, especially since P/B is a highly group-oriented practice and the major loss of life coupled with scarcity of food and other resources might well have seriously eroded the social fabric -- as documented by Turnbull for the Ik. It could also have affected their woodworking and mask making traditions since many if not all the old rituals might have been suspended during a period when survival may have depended, literally, on the survival of the strongest and most ruthless, rather than the most cooperative and selfless, which would have been the traditional HMC ethic.

So the gap we now see centered in India, might well represent a displacement of a gap that really began farther east -- and was transmitted to India over time by neighboring groups east of the border that eventually migrated there. It's important to remember that a great many groups now living in East and Southeast Asia have also lost many of the same African traditions, probably as a result of the same disastrous event, so it would be a mistake to locate the gap only in South Asia.

Survivals of the old HMC traditions, at least the musical ones, can be found today largely among marginalized groups living in isolated refuge areas, in a vast region stretching from the Malay Peninsula to Indonesia, the Philippines and Melanesia, and also northward among certain tribal groups of South China and Taiwan. Since we see so many of the old African traditions (and often African morphology as well) among such groups, it's not difficult to conclude that they must originally have been located far enough to the east to suffer least from the effects of Toba (or other disaster based in the same area) and thus manage to hold on to most (though clearly not all) of their original traditions.

5. ca 70,000 - 40,000 ya. As the genetic evidence suggests, the population of India seems to have undergone a major expansion at some point after the Out of Africa migration. But the same evidence, in which very few haplotypes characteristic of the oldest populations of the subcontinent can be found elsewhere, suggests that there was very little migration elsewhere. As the maps suggest, India seems to have been relatively self-contained during most of the paleolithic and neolithic as well. Many groups migrated into the region but few seem to have migrated out. It could be that the lack of migration elsewhere contributed to the accumulation of population within one large but constricted area. It's also possible that the same disaster that produced the bottleneck(s) may have wiped out what could have been a large population of pre-modern humans, Neanderthals or Homo Erectus, thus elimating competition for resources in this region, as Homo Sapiens from the west and east resettled there.

6. ca. 60,000 - 20,000. According to the maps I posted, revealing population clines emanating from East Asia in all directions, but mainly from the southeast to the northwest, it looks as though there were major migrations into Central Asia and probably also directly north to Siberia at various points during this very long period.

Most of this entire region, from Southeast Asia to Northeast Asia, north to Siberia and northwest to Central Asia is now dominated by solo singing, or else group singing in unison or heterophony, in a manner radically different from anything we find in Africa today (aside from groups heavily influenced by Islam). This is the dominant style in India as well, even among the lower castes. The tribal groups of India have somewhat different styles, less oriented toward solo singing and with some traces of polyphony, but nevertheless very different from P/B.

It's possible that this style, often dominated by elaborate and virtuosic solo singing with heterophonic instrumental accompaniment, originated as part of the radically altered culture of a single surviving founder group, spreading with them as they expanded throughout the East in all directions, a process that probably began during the Paleolithic and extended well into the Neolithic as their most aggressive and warlike descendants ultimately subjugated those weaker or less aggressive, with those least willing or able to submit heading for sanctuaries in the hills and/or dense forests. Those groups that we now find only in the most remote, isolated regions may well have at one time dominated much of Asia to the east and south of India, but would have been forced to the margins by the same conquerers who eventually subjugated everyone else.

4. ca 73,000 - 70,000 ya: Assuming a bottleneck or bottlenecks after Toba, or some other disaster in the same region, we can't be sure how many such bottlenecks would have occurred. It's even conceivable that only one group might have survived in the general area, either in India itself or to the east. Or possibly there were many groups with at least a few survivors, and thus many different founder effects. It's also very difficult if not impossible to correlate such founder effects with the genetic evidence. A major disaster at that time may well have produced one or many population bottlenecks by destroying human life en masse, but we have no reason to assume it would have produced even a single mutation. So it would be a mistake to read a separate founder effect into each different branch of M, N, or R.

Following Oppenheimer, I will at this point explore the possibility he raises, that the eruption would have completely destroyed all humans caught within range of the thickest fallout, which means that the tribal (and many of the lower caste) populations we now see in India originated either west or east of the subcontinent, from where various scenarios of repopulation would have occurred. If the pocket we identified in the northwest Punjab-Kashmir region survived, then west India might have been repopulated from there. As for repopulation from the east, any groups living just east of India during the Toba blast would almost certainly have suffered serious bottlenecks and may well have lost at least some of their original African traditions.

This could explain the absence of significant P/B characteristics in their music, especially since P/B is a highly group-oriented practice and the major loss of life coupled with scarcity of food and other resources might well have seriously eroded the social fabric -- as documented by Turnbull for the Ik. It could also have affected their woodworking and mask making traditions since many if not all the old rituals might have been suspended during a period when survival may have depended, literally, on the survival of the strongest and most ruthless, rather than the most cooperative and selfless, which would have been the traditional HMC ethic.

So the gap we now see centered in India, might well represent a displacement of a gap that really began farther east -- and was transmitted to India over time by neighboring groups east of the border that eventually migrated there. It's important to remember that a great many groups now living in East and Southeast Asia have also lost many of the same African traditions, probably as a result of the same disastrous event, so it would be a mistake to locate the gap only in South Asia.

Survivals of the old HMC traditions, at least the musical ones, can be found today largely among marginalized groups living in isolated refuge areas, in a vast region stretching from the Malay Peninsula to Indonesia, the Philippines and Melanesia, and also northward among certain tribal groups of South China and Taiwan. Since we see so many of the old African traditions (and often African morphology as well) among such groups, it's not difficult to conclude that they must originally have been located far enough to the east to suffer least from the effects of Toba (or other disaster based in the same area) and thus manage to hold on to most (though clearly not all) of their original traditions.

5. ca 70,000 - 40,000 ya. As the genetic evidence suggests, the population of India seems to have undergone a major expansion at some point after the Out of Africa migration. But the same evidence, in which very few haplotypes characteristic of the oldest populations of the subcontinent can be found elsewhere, suggests that there was very little migration elsewhere. As the maps suggest, India seems to have been relatively self-contained during most of the paleolithic and neolithic as well. Many groups migrated into the region but few seem to have migrated out. It could be that the lack of migration elsewhere contributed to the accumulation of population within one large but constricted area. It's also possible that the same disaster that produced the bottleneck(s) may have wiped out what could have been a large population of pre-modern humans, Neanderthals or Homo Erectus, thus elimating competition for resources in this region, as Homo Sapiens from the west and east resettled there.

6. ca. 60,000 - 20,000. According to the maps I posted, revealing population clines emanating from East Asia in all directions, but mainly from the southeast to the northwest, it looks as though there were major migrations into Central Asia and probably also directly north to Siberia at various points during this very long period.

Most of this entire region, from Southeast Asia to Northeast Asia, north to Siberia and northwest to Central Asia is now dominated by solo singing, or else group singing in unison or heterophony, in a manner radically different from anything we find in Africa today (aside from groups heavily influenced by Islam). This is the dominant style in India as well, even among the lower castes. The tribal groups of India have somewhat different styles, less oriented toward solo singing and with some traces of polyphony, but nevertheless very different from P/B.

It's possible that this style, often dominated by elaborate and virtuosic solo singing with heterophonic instrumental accompaniment, originated as part of the radically altered culture of a single surviving founder group, spreading with them as they expanded throughout the East in all directions, a process that probably began during the Paleolithic and extended well into the Neolithic as their most aggressive and warlike descendants ultimately subjugated those weaker or less aggressive, with those least willing or able to submit heading for sanctuaries in the hills and/or dense forests. Those groups that we now find only in the most remote, isolated regions may well have at one time dominated much of Asia to the east and south of India, but would have been forced to the margins by the same conquerers who eventually subjugated everyone else.

Thursday, January 21, 2010

294. Aftermath 9: The Later Migrations

Before continuing with my "Later Migrations" scenario, I want to alert you to a couple things. First, Maju, has been posting some extremely interesting and relevant comments based on his own extensive research into the genetic evidence, particularly the phylogenetic trees for mtDNA haplogroups M and N and their derivative clades. Since he doesn't always agree with me, and has a more complete grasp of the genetic evidence than I do anyhow, I urge you to read what he has to say to get an informed and independent perspective. (Actually we aren't in total disagreement either, since we both agree that the evidence is not yet complete, and never easy to interpret.) Anyone seriously interested in the genetic evidence pertaining to the later migrations I've been speculating about should read his comments, especially those for Post 291. Keep a lookout for some of the links he's posted to his blog, which is extremely rich in all sorts of interesting details and discussions of the genetic evidence (also some excellent political commentary, which I usually happen to agree with).

Second, I was reminded by one of the links on Maju's blog (Leherensuge) of an especially relevant article, dating from 2005, The Dazzling Array of Basal Branches in the mtDNA Macrohaplogroup M from India as Inferred from Complete Genomes, by Chang Sun et al. I'd read through this one already, but failed to notice an important detail, the Age Estimations for Haplogroup M, presented in Table 1:

This method averaged out to a "better" result, 54.1 k years ago, but this date still makes the M's of India younger than the others. What also caught my attention was the fact that, of all the haplogroups represented in the Chenchu/Koya study, the three most clearly centered in the south and east are by far the oldest: M2a at 70.2 k ya; M2b at 77.1 k ya. Most notably, M6b, centered not only in the south and east, but also the extreme northwest (farthest from Toba), where we find so many tone languages, was found to be roughly 92.5 k years old! So not only are the M's of India younger than those of the other regions along the southern route, but the oldest ones in the subcontinent are closest to those regions that either would have been least affected by the Toba ash cloud, or, according to the theory put forth by Oppenheimer, are likely to have been resettled by groups migrating westward from Southeast Asia in the wake of the Toba event, after the natural environment of the region had once again become inhabitable.

South Asia 44.6 k yaThough I feel sure Maju will complain that once again I'm concentrating too much on that which suits my purpose, it's impossible for me to ignore this additional evidence for a genetic gap exactly where I see a very significant cultural gap. For reasons that the authors themselves find difficult to explain, the M haplogroups confined mostly to South Asia are estimated by their own procedures to be significantly younger than those for East Asia, Oceania or Southeast Asia. To be consistent with a straightforward, continuous Out of Africa scenario, they should be older than the others, not younger. A very similar result was obtained by Soares et al (see Post 262 for discussion). To be fair, I'll quote their explanation for what to them is clearly an anomaly:

East Asiaa 69.3 k ya

Oceania 73.0 k ya

SE Asia 55.7 k ya

The abnormal younger age (~44 x 10 cubed years) of the Indian M lineages may be attributed to the unequal age contributions from different M haplogroups to the total M age estimate. The frequency composition of the particular M haplogroups in a population sample from India then matters a lot because the ages contributed by the different branches range from 21 x 10 cubed years (M30a) to 93 x 10 cubed years (M6b). Our sample drawn for complete sequencing does not reflect the natural frequencies and therefore could bias the age estimation.

To investigate this, we simulated a natural frequency distribution by assigning the mtDNAs sampled from the Chenchu and Koya populations (Kivisild et al. 2003) to

their respective haplogroups by (near) matching control region motifs (Yao et al. 2002). Fewer than 5% of the mtDNAs were virtually unassignable, so that the remaining 142 mtDNAs could be used to evaluate the natural frequency of each M branch in [the] Indian population (table 2).

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

293. Aftermath 8: The Later Migrations

Let's take yet another look at the fascinating "isofrequency maps" produced by Mait Metspalu et al:

From the caption:

Maps B and C especially tell a remarkable story, which, I must confess I was not quite prepared for. Given the Toba scenario I've been exploring (which remains hypothetical, as I hope everyone reading here understands), I'd assumed that the resulting "bottlenecks" would have led to fundamental changes, away from the typically African characteristics of HMP, toward those more typical of what we now see among most (though not all) of the various "races" and large-scale "ethnic" subdivisions of Asia, Europe, etc. I still see this as a likely possibility.

However, since India would have borne the brunt of the disaster, it seemed likely that India would have been the principal staging ground for the migrations that would have spread the newly altered genetic/cultural lineages to the four corners of the world. This was the scenario I presented in my "Echoes" essay. But maps B and C tell a different story. According to map B, India has remained relatively isolated, while the scenario implied in map C suggests a massive migration based to the east of India, and spreading both north and northwest from there, with the Himalayas as a significant barrier, channeling the migrants away from India and in the direction of Central Asia and, ultimately, Europe.

Another map, Figure 5 from the same paper, is explicitly devoted to the migration pathways:

From the caption:

Peopling of Eurasia. Map of Eurasia and northeastern Africa depicting the peopling of Eurasia as inferred from the extant mtDNA phylogeny. . . [T]he initial split between West and East Eurasian mtDNAs is postulated between the Indus Valley and Southwest Asia. Spheres depict expansion zones where, after the initial (coastal) peopling of the continent, local branches of the mtDNA tree (haplogroups given in the spheres) arose (ca. 40,000 – 60,000 ybp), and from where they where further carried into the interior of the continent (thinner black arrows). Admixture between the expansion zones has been surprisingly limited ever since.While the authors seem principally intent on demonstrating the likelihood of the "southern route" over the northern one (and imo their demonstration is extremely convincing), the picture they provide here of the later migrations is equally compelling, in my view.

Though it's extremely difficult to account for every aspect of the genetic picture in terms consistent with the Toba hypothesis (or any other hypothesis, for that matter), I'd like to propose the following, provisional, scenario:

1. 85,000 to 75,000 ya: Exit of HMP from Africa, and migration eastward through South Asia to Southeast Asia and beyond, following the southern route.

2. 74,000 ya: Toba explosion, decimating or completely destroying all migrant settlements in South Asia.

3. 74,000 ya: Population bottlenecks produced by the disaster, with varying degrees of intensity depending on how close each population is to the ash plume. The effect of each bottleneck will be different, depending on completely unpredictable circumstances associated with each group affected. In each case, either the group or its lineage does not survive at all, or, if it does survive, its character, both physical and cultural, will be determined by the unique qualities of each new founder group.

(to be continued . . .)

Monday, January 18, 2010

292. Aftermath 7

To give us a closer look, I've blown up the map representing the fallout from the Toba explosion (based on the distribution of Toba tephra found at several archaeological sites, both in and outside of India -- from Stephen Oppenheimer's Journey of Mankind) and placed it just above Map C from the article we've been discussing, which represents "the spatial frequency distribution of mtDNA haplogroups native to East Eurasia." The red dot on the upper map represents the location of Toba, in northwest Sumatra. The northernmost tip of Sumatra can just barely be seen at the bottom of the lower map.

My idea, which is looking even better to me now, was that this would have been a likely spot where a branch of the Out of Africa migrants, who could have broken from the main group to travel north along the banks of the Indus, might have been able to survive the effects of Toba with their African traditions more or less intact. If tone language was part of their tradition, then that would explain the presence of tone language in this area today, as a survival. The survival of such a group in such an area might also explain how certain elements of the "African signature" made it to Europe, including some very important P/B related traditions still found in refuge areas throughout that continent. This is certainly among the most speculative of my speculations, and should be taken with a huge grain of salt -- but nevertheless, the African musical traditions are present in Europe, and must be explained.

My idea, which is looking even better to me now, was that this would have been a likely spot where a branch of the Out of Africa migrants, who could have broken from the main group to travel north along the banks of the Indus, might have been able to survive the effects of Toba with their African traditions more or less intact. If tone language was part of their tradition, then that would explain the presence of tone language in this area today, as a survival. The survival of such a group in such an area might also explain how certain elements of the "African signature" made it to Europe, including some very important P/B related traditions still found in refuge areas throughout that continent. This is certainly among the most speculative of my speculations, and should be taken with a huge grain of salt -- but nevertheless, the African musical traditions are present in Europe, and must be explained.

The match between the ash cloud and the negative space formed by the haplogroup distribution is remarkable. Note also that the outer edges of the Toba cloud perfectly match the distribution cline to its northeast. Since there are no significant natural borders along the coastal route, and no other readily apparent explanation for the genetic segregation of the two areas, it's certainly tempting to attribute the pattern we see in the lower map to the event represented in the upper. And, if Petraglia is correct in attributing the artifacts he found among Toba tephra to modern humans, then the association becomes impossible to ignore.

Toba would not only explain the discontinuity between India and points east, so evident on the genetic maps, but also the gap I've been stressing for so long, involving certain cultural practices (not only musical, but also artistic and possibly linguistic as well) found in both Africa and greater Southeast Asia, but almost completely absent from the Middle East, Pakistan and India. African-related cultural survivals can indeed be found in exactly those areas that would have been upwind from the eruption and thus relatively unaffected.

It might also explain the strange distribution of both M and N-related haplogroups in South Asia. As Oppenheimer noted, and Metspalu et al confirmed, there is a distinct northwest to southeast cline in the distribution of M, with most instances by far to be found along the eastern and southern coasts. N-derived haplogroups, on the other hand, are relatively rare in this region, though common in the west and northwest of India -- and also farther east, beyond the border with Myanmar. Oppenheimer associates this puzzling distribution with the Toba event, suggesting that the prolonged ash cloud could have devastated all or most of India, especially both M and N related populations in the east and south, closest to the volcano. He hypothesizes that this area could then have been repopulated by M dominated groups immigrating from the east, who might then have spread, in a cline, to the rest of the subcontinent, while N-related groups to the west could have repopulated India from that region. This could have left India populated by more recent M and N hapolotypes than those found farther east, a pattern noted by both Cordaux et al and Soares et al, as reported here earlier.

It's also interesting to speculate about the very interesting distribution of haplogroups M6 and M6b, in the maps from Metspalu et al that I've already posted:

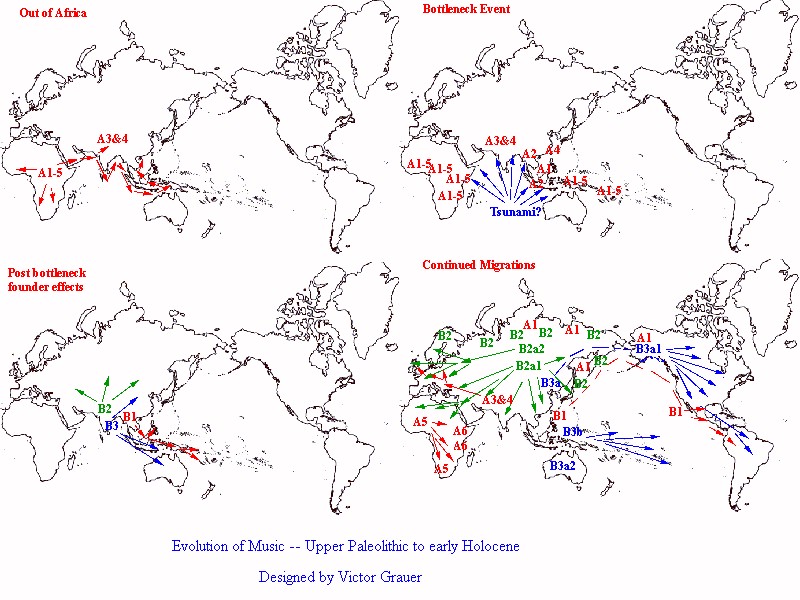

The pattern is clear from the map at the upper left, where the heaviest distribution of M6 is found in two widely different places, not only the south and east of India, but also far to the northwest, in the Punjab-Kashmir region shared with Pakistan. There are two things about this region that make it especially interesting: its location places it at a greater distance from Toba than any other part of South Asia, and it is the only region between Africa and East Asia where tone languages are commonly found. It also happens to be, very roughly, the same region where I placed some hypothetical survivals of P/B musical style in the set of maps I presented in association with my phylogenetic map of world music, all the way back in Post 12. See the location of A3 and A4 in the map titled "Bottleneck Event":

My idea, which is looking even better to me now, was that this would have been a likely spot where a branch of the Out of Africa migrants, who could have broken from the main group to travel north along the banks of the Indus, might have been able to survive the effects of Toba with their African traditions more or less intact. If tone language was part of their tradition, then that would explain the presence of tone language in this area today, as a survival. The survival of such a group in such an area might also explain how certain elements of the "African signature" made it to Europe, including some very important P/B related traditions still found in refuge areas throughout that continent. This is certainly among the most speculative of my speculations, and should be taken with a huge grain of salt -- but nevertheless, the African musical traditions are present in Europe, and must be explained.