(. . . continued from previous post.)

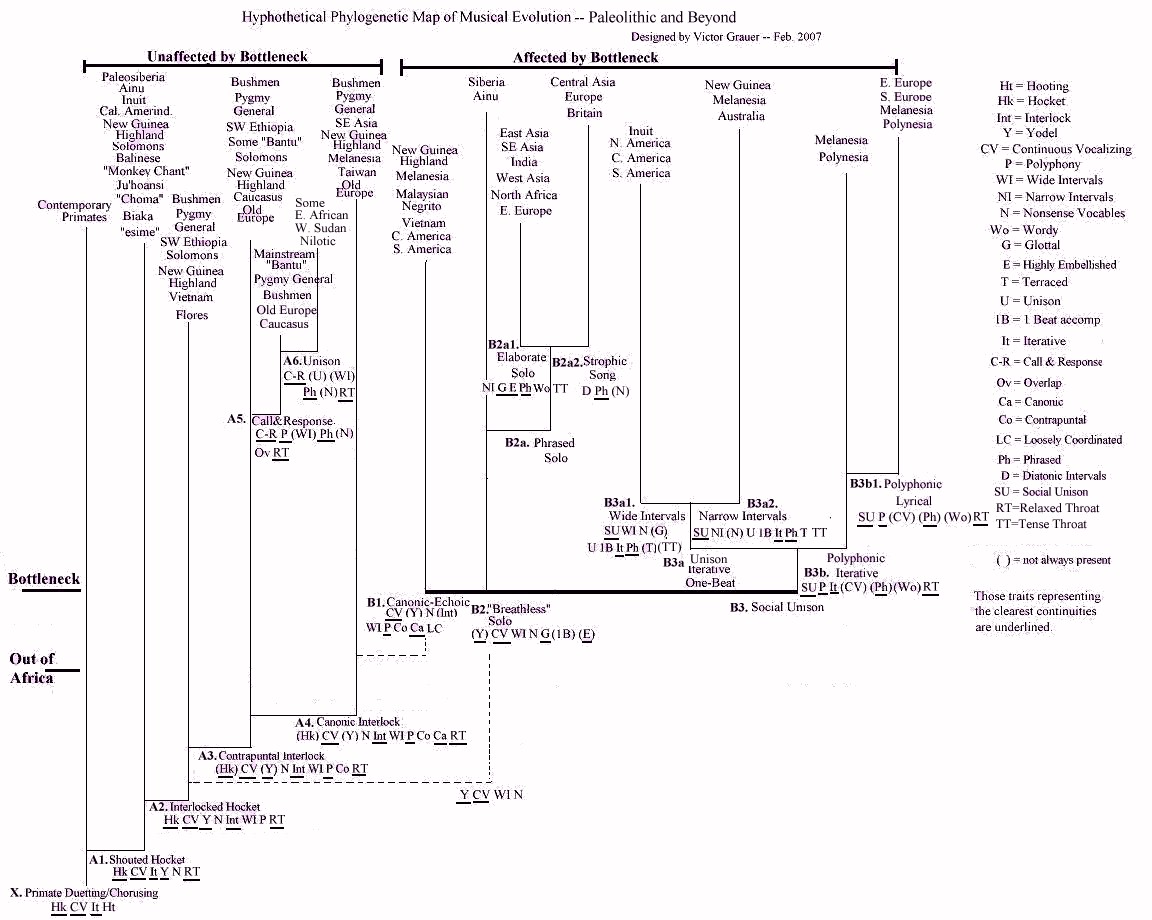

What's implied in my phylogenetic tree is that the traditional, highly interactive, musical style brought out of Africa by HMP (the "Hypothetical Migrant Population") could have been seriously disrupted due to some major population bottlenecks produced by a serious and wide-ranging disaster, centered roughly in South Asia, at a time when relatively small colonies of migrants would have been spread out over much of the Indian Ocean coast. Such an event could account for at least some of the major discontinuities we see when we examine the traditional musical styles of so many societies in various parts of the world today. My tree focuses on three distinctive proto-styles, B1, B2 and B3, that could have emerged from such an event, but there could have been some others as well -- my phylogeny may well be far from complete.

To understand how the distinctive, and actually quite remarkable "unison/ iterative/ one-beat" style of the Australian Aboriginals could have originated, we need to look first at its predecessor: B3. B3, or "Social Unison" can be seen as prototypical for a great many musical sub-styles now found largely in Oceania (including Australia), with possible relatives in Eastern and Southern Europe, and an important branch in the Americas. We can hypothesize either that B3 originated among a single, very small, group of disaster survivors probably living somewhere to the east of India, and then spread to other regions of Asia, Europe, Oceania and the Americas as the descendants of this population expanded in all directions over thousands of years; or, and probably more likely, that various versions of B3 arose more or less simultaneously among different groups living in roughly the same area, and spread in various directions as the descendants of those groups expanded.

What all such cases would have had in common would have been a serious disruption of social life resulting from the disaster. Since P/B is so dependent on the close and even intimate interaction of all participants, it's not difficult to see how such a style could have vanished in the face of serious adversity of a sort that could have pitted formerly cooperative families and individuals against one another in a desperate struggle for survival. After the dust cleared, and social life began to return to normality, efforts to revive ancestral traditions may well have been hampered by the disruption of the normal process of cultural transmission from one generation to the next. So it's not difficult to see how simpler musical traditions, such as the various versions of B3, could have emerged.

Among some groups, interlocked polyphonic vocalizing may have given way to simple leader-chorus alternation or, among others, social unison -- in some cases with the retention of polyphony in the form of parallel harmonies or drone effects, while in other cases the newly emergent society may have completely lost its ability to sing in harmony -- or alternatively, dismissed the harmonizing of neighboring groups as a crudely "primitive" practice to be avoided at all costs in favor of a more carefully controlled and constrained approach to solo singing, and/or the development of precisely synchronized unison vocalizing. (It's important to recognize that among many such groups unison is not merely due to an inability to harmonize, but that even incidental harmonizations are seen as mistakes to be avoided.)

It is on such a basis that we can see Australian Aboriginal style (B3a2), and it's close relatives in New Guinea and Island Melanesia, emerging. Not necessarily as a direct result of the same bottleneck that would appear to have produced the "Australoid" morphology, but as a development from it, i.e., as a development from the proto-style I've called B3. Since we do not currently find B3a2 among any South Asian tribal groups or, indeed, any musical traditions now known between India and East Indonesia (to the best of my knowledge), it's tempting to assume that B3a2 may have originated in the Sahul itself, possibly due to the population bottleneck that would have occurred when the first wave of Australoid males invaded, thousands of years after the initial "Negrito" settlement of that continent.

There is a problem with that scenario, however, due to the fact that B3a2 has a "sister" clade, B3a1, which turns out to be the dominant musical style for almost all of native North America, and much of Central and South America as well. The two substyles can sound very similar, especially when Australian Aboriginal singing is compared with Plains Indian singing, an especially close match in melodic type along with everything else. The principal difference is that Australians tend to emphasize relatively narrow intervals in their melodies, whereas Amerindians prefer wide intervals, such as thirds, fourths and fifths. Harsh, tense-voiced unison singing, with frequent iteration of the same note, accompanied by a single, repeated beat on either drums or rattles (Indians) or percussion sticks (Australians) tends to be the rule in both traditions. There are important differences as well, especially since drums of any kind appear to be unknown in Australia, while extremely important in the Americas. And there is no equivalent of the Didgeridoo in the Americas.

Do both traditions stem from a common root? Or are the many resemblances coincidental? If they do in fact stem from a common root, which seems likely, then it's necessary to place the origin of this style early enough to account for what would have to have been a very early divergence between the ancestors of the two groups, which are, of course (and this adds to the problematic aspect of this association), very different morphologically. Genetically, however, there does seem to be a link, since the Y chromosome C haplogroup is in fact found in all the Asiatic/Oceanic B3 groups in my musical tree. And, as German Dziebel has recently reminded me, a Cantometric factor analysis done by Alan Lomax back in 1980 united many Amerindian groups with Australian Aboriginals as part of what he termed a Circum-Pacific family. According to Lomax, "In East and Southeast Asia the rise of high Chinese, Indo-Chinese, Malaysian and Polynesian high culture obscures a tradition that seems to have once stretched uninterruptedly from Siberia south to Australia. The Circum-Pacific model still shapes the performances of aboriginal Australia, much of Melanesia and parts of backwoods Malaysia . . . ("Factors of Musical Style," in Theory and Practice: Essays Presented to Gene Weltfish, ed. S. Diamond, p. 37). If Lomax is right, then North America and Australia could be regarded as enormous refuge areas, populated during a period when more advanced Neolithic societies were beginning to expand, pushing their hunter-gatherer neighbors increasingly into peripheral areas.