The match between the ash cloud and the negative space formed by the haplogroup distribution is remarkable. Note also that the outer edges of the Toba cloud perfectly match the distribution cline to its northeast. Since there are no significant natural borders along the coastal route, and no other readily apparent explanation for the genetic segregation of the two areas, it's certainly tempting to attribute the pattern we see in the lower map to the event represented in the upper. And, if Petraglia is correct in attributing the artifacts he found among Toba tephra to modern humans, then the association becomes impossible to ignore.

Toba would not only explain the discontinuity between India and points east, so evident on the genetic maps, but also the gap I've been stressing for so long, involving certain cultural practices (not only musical, but also artistic and possibly linguistic as well) found in both Africa and greater Southeast Asia, but almost completely absent from the Middle East, Pakistan and India. African-related cultural survivals can indeed be found in exactly those areas that would have been upwind from the eruption and thus relatively unaffected.

It might also explain the strange distribution of both M and N-related haplogroups in South Asia. As Oppenheimer noted, and Metspalu et al confirmed, there is a distinct northwest to southeast cline in the distribution of M, with most instances by far to be found along the eastern and southern coasts. N-derived haplogroups, on the other hand, are relatively rare in this region, though common in the west and northwest of India -- and also farther east, beyond the border with Myanmar. Oppenheimer associates this puzzling distribution with the Toba event, suggesting that the prolonged ash cloud could have devastated all or most of India, especially both M and N related populations in the east and south, closest to the volcano. He hypothesizes that this area could then have been repopulated by M dominated groups immigrating from the east, who might then have spread, in a cline, to the rest of the subcontinent, while N-related groups to the west could have repopulated India from that region. This could have left India populated by more recent M and N hapolotypes than those found farther east, a pattern noted by both Cordaux et al and Soares et al, as reported here earlier.

It's also interesting to speculate about the very interesting distribution of haplogroups M6 and M6b, in the maps from Metspalu et al that I've already posted:

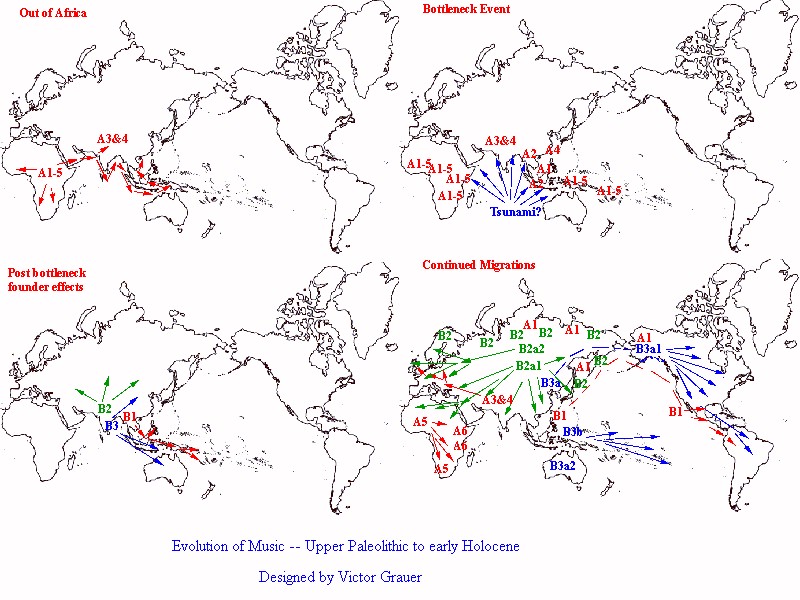

The pattern is clear from the map at the upper left, where the heaviest distribution of M6 is found in two widely different places, not only the south and east of India, but also far to the northwest, in the Punjab-Kashmir region shared with Pakistan. There are two things about this region that make it especially interesting: its location places it at a greater distance from Toba than any other part of South Asia, and it is the only region between Africa and East Asia where tone languages are commonly found. It also happens to be, very roughly, the same region where I placed some hypothetical survivals of P/B musical style in the set of maps I presented in association with my phylogenetic map of world music, all the way back in Post 12. See the location of A3 and A4 in the map titled "Bottleneck Event":

My idea, which is looking even better to me now, was that this would have been a likely spot where a branch of the Out of Africa migrants, who could have broken from the main group to travel north along the banks of the Indus, might have been able to survive the effects of Toba with their African traditions more or less intact. If tone language was part of their tradition, then that would explain the presence of tone language in this area today, as a survival. The survival of such a group in such an area might also explain how certain elements of the "African signature" made it to Europe, including some very important P/B related traditions still found in refuge areas throughout that continent. This is certainly among the most speculative of my speculations, and should be taken with a huge grain of salt -- but nevertheless, the African musical traditions are present in Europe, and must be explained.

My idea, which is looking even better to me now, was that this would have been a likely spot where a branch of the Out of Africa migrants, who could have broken from the main group to travel north along the banks of the Indus, might have been able to survive the effects of Toba with their African traditions more or less intact. If tone language was part of their tradition, then that would explain the presence of tone language in this area today, as a survival. The survival of such a group in such an area might also explain how certain elements of the "African signature" made it to Europe, including some very important P/B related traditions still found in refuge areas throughout that continent. This is certainly among the most speculative of my speculations, and should be taken with a huge grain of salt -- but nevertheless, the African musical traditions are present in Europe, and must be explained.As for putting all the various pieces of the puzzle together, it is, admittedly, not always easy to reconcile all the details of the various genetic distributions in this vast region with an event such as the Toba eruption, but the explanatory power of this event is potentially so strong that further research is certainly justified. Toba can no longer be on the back burner, it must come to the forefront of our attention.

No comments:

Post a Comment