Wednesday, February 24, 2010

315. Update

The exploratory overview that began with Post 225 is now complete -- or at least as complete as I feel capable of dealing with at the moment. There are other aspects of this scenario that I'd still like to explore, especially questions pertaining to the origin of competition and violence, which, as should be clear by now, were conspicuously absent from the value system of our MRCA (Most Recent Common Ancestors -- aka HBP). But at this point I feel the need to concentrate on other matters -- primarily the three Cantometrics-based research projects to which I am currently committed, with three different sets of collaborators. (The work continues to progress on all fronts -- slooowwwwwly but surely.) And also a paper I'm preparing, based on some of the ideas I've been posting here. I feel the need to get all these thoughts together in a more coherent form and also to get them out there into the "real world" beyond the blogosphere. I'm hoping to put together something suitable for a "mainstream" anthropological journal, despite the apparent disdain such journals have traditionally had for the sort of things I've been up to. Guess I'm just an eternal optimist, but I have a feeling that the time is ripe for some major changes on that front. So wish me luck.

I want to thank everyone who's been reading here. Statcounter tells me there are several of you who are regular followers, though only a few have made the effort to comment. And the hit count is rapidly closing in on 60,000. Not bad for such an esoteric blog. I also want to thank German and Maju, who have contributed considerably with their frequent, and often very helpful comments, even when they disagree. I am grateful for their interest and their involvement.

I won't be posting as often as before, at least for the time being. Though I may post from time to time to report on new developments that have caught my attention, or to update everyone on my activities.

That's all for now, folks.

l8r

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

314. A Cantometric Study

Last month, purely by accident, while browsing the Web, I came across a remarkable paper based on, of all things, Cantometrics.* It's actually a Master's Thesis, from the University of London and Imperial College, and is surprisingly recent, dating from March 2006. I assumed I was aware of everything going on in the world of Cantometrics, but this one took me by surprise. It's called Finding the Blues: An Investigation into the Origins of African American Music. The author is a young man named George Busby, whose work was supervised by Dr. Armand Leroi, a noted biologist with a special interest in world music and Cantometrics. To my great surprise, delight and astonishment, Busby, with the assistance of statistician Jonathan Swire, has done a truly exemplary job.

Normally I would not look forward to reading a Cantometric study done without my assistance, because the system is not as straightforward as it might seem and there are certain quirks and hidden pitfalls that must be taken into consideration before any meaningful statistics can be produced. Amazingly, Busby and Swire figured out literally all the problems and were able to iron out just about all the kinks, a job that involved, among other things, recasting certain parameters entirely. I would do things a bit differently, but I have no complaints about the approach they took. In fact, as far as I'm concerned, this paper can stand as a model for how to use Cantometrics effectively as a tool for cross-cultural research. I'll call your attention specifically to the Appendices, starting on p. 28, which contain a wealth of extremely useful information on the background of Cantometrics, its methodology, its problems, what makes it controversial, how it works, and how to get the most out of it.

For someone new to this methodology, Busby seems remarkably perceptive in understanding the value of Cantometrics and evaluating both its strengths and weaknesses. Here are some excerpts from his paper that I found particularly relevant:

The phylogenetic study of song requires song analysis in a way that can produce readily comparable data. A profile of numbers for a song (which refers to its characteristics) needs to be produced so that its similarities to other songs can be quantitatively investigated. This is analogous to the production of genetic profiles from DNA for investigating evolutionary hypotheses. Fortunately data of this type are already available from a world sample of folk and tribal music collated for the Cantometrics experiment of the 1960s. . .The algorithm shows clearly that multivariate analysis of the Cantometric data can produce structure that matches closely to geographical, historical and cultural populations. Note also that some clusters are highly biased to one cultural region while others contain a mixture, for example in K = 7, cluster 4 is mainly AI, while cluster 7 has a combination of styles, AAF and OEU, in almost equal proportions. It must be inferred from these results that the song styles from the two regions are similar. . .Alan Lomax developed Cantometrics with the conviction that song style around the world could be explained by the culture in which it was produced. His idea, that song is a measure of culture, was a bold one. At the time, it had its critics. The methodology was questionable, the analysis perhaps naïve (see appendix A1). However, the present study has sought to overcome many of these problems, particularly regarding our removal of a priori cultural information from the analysis and the quantitative techniques used in the cluster analysis. In the light of recent cultural evolutionary research, Lomax’s idea now seems prescient. . .From the initial analysis they had the two broad types which, as the study evolved, were divided into subsets of types depending on these factors of song style performance. Different combinations of levels of factors gave different profiles and so songs could be quantitatively rated on how similar they were. As well as the measures mentioned above, the songs were graded on their cohesion, wordiness, metre, embellishment and type of voice (clear or slurred). Factor analysis produces clusters of songs with similar profiles for these traits. Interestingly, these clusters matched, albeit very generally, geographically and historically similar areas. That is to say, song styles from African Hunter societies were more similar to each other than they were to Amerindian or European songs. This crude system was improved and eight major taxonomic concepts were discovered, each with different scales beneath them (table A1.1.).Musicologists were already aware of these world song style regions, so it’s not wholly surprising that Cantometrics confirmed this. However, it is important to note that it did find these areas in a quantitative and scientific fashion (Merriam 1969).

There is much more of interest in this paper, not the least of which is what Cantometrics enabled the author to discover about the relation between African music, African American music and the Blues, which is, of course, the principal topic. It pleases me enormously to see such an outstanding piece of Cantometrics-based research by a young person who understands the value of this much maligned and little understood methodology.

Mr. Busby's current activities are documented on the very interesting Capelli Group website, where it soon becomes clear that he is, very sadly, no longer involved in musicological studies. Though he is now pursuing an equally interesting -- and not unrelated -- field: evolutionary genetics. I wish him well and hope that someday we might find a way to work together.

*Cantometrics is a computerized method for the comparative study of world vocal music, conceived by Alan Lomax and developed by Lomax and myself during the summer of 1961 (yes, I am THAT old :-\). For more information, see Post 76 et seq.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

313. Alternatives

(. . . continued from previous post.)

One might suppose that the simplest and most logical alternative explanation for the different types of human morphology, culture and music would be based on the oldest and most extreme version of the multiregional model, where it is assumed that both language and music were independently invented at different times in different parts of the world, among "archaic" humans who can also be seen as "racial" prototypes. Thus one might argue that the distinctive unison/ iterative/ one-beat musical style of Australia could have originated as a completely independent invention among some "Australoid" Homo Erectus group somewhere in South or Southeast Asia; that solo oriented, embellished vocalizing could have originated among a group of "proto-mongoloid" Homo Erectus somewhere in East Asia, leading to the development of Lomax's "elaborate-style"; that the various types of drone polyphony so commonly found among certain indigenous groups in Southeast Asia, Island Southeast Asia and Polynesia could have originated somewhere in that part of the world, among yet another Homo Erectus group; that the strophic song, ballad and epic could have originated independently somewhere in Europe or Central Asia, among some "proto-caucasoid" Neanderthal group; etc.

The wide distribution of P/B style and its variants among so many isolated indigenous groups of varying morphologies could, according to the same model, be seen as the survival of a truly archaic tradition dating back, not tens of thousands but literally hundreds of thousands, or even millions of years, to the origin of "Homo Sapiens" as a distinct species (which, according to the multiregional model, would have included Homo Erectus as a distinct type, but not a separate species), also in Africa, but millions of years ago, which would date P/B to millions of years before the advent of the ancestral group I call HBP.

If I had to choose among the various alternatives presented in the last three posts, purely on the basis of the musical evidence, I would definitely pick this version of multiregionalism, since it does appear to account for much of the diversity we see in the world of today and very neatly "solves" at least some (though certainly not all) of the riddles I've been struggling with. Unfortunately, even the most enthusiastic proponents of multiregionalism have been forced to back away from this, the most extreme version, since 1. it cannot account for all the many similarities we see among all the various human populations; 2. it depends on an unlikely model of biological and cultural convergence that was once very fashionable, but most evolutionists now reject; 3. it is completely inconsistent with the genetic evidence, which reveals no sign of biological convergence, or indeed any type of hybridization between Homo Sapiens, Neanderthals or Homo Erectus.

Newer, more or less compromised, versions of multiculturalism have arisen, based on various attempts to accommodate aspects of the Out of Africa model. The most recent, and most widely accepted (among the relatively small group still promoting the multiregional view), is probably the one offered by Vinayak Eswaran in his essay A Diffusion Wave Out of Africa. Eswaran's highly imaginative, if not fanciful, theory is so complex and so full of tortuous arguments and caveats as to defy my powers of paraphrase and summary, so I hope he'll forgive me if I misrepresent him. In essence, what it amounts to is an "Out of Africa" theory based not on migration but on a "diffusion wave" that would have transmitted genetic materials through a series of localized encounters between adjacent groups spanning all regions of Africa, Asia and Europe over a very long period of time.

He sees anatomically modern humans evolving first in Africa, in accordance with the now prevailing view, but according to his model, their modern genotypes were transmitted via a kind of daisy chain exchange of sexual partners across vast regions of time and space, a process driven by certain physical advantages of the modern anatomy that would, over time, have preserved the "modern" geno and pheno types through natural selection while causing the more archaic anatomy to gradually disappear. Eswaran's theory may or may not make sense, depending on one's tolerance for mathematically driven models, but he has so little to say about the cultural side of his diffusion wave that it's not clear what we are supposed to think regarding the origins and peregrinations of stone tools, hunting methods, language families, or musical styles.

While traditional multiregionalism remains far too problematic and Eswaran's version far too speculative, there are simpler variants that are potentially more convincing. For example, what if there could have been some degree of significant friendly contact between Homo Sapiens and Homo Erectus during the initial Out of Africa trek? The possibility of some degree of interbreeding can't be completely ruled out, but what interests me more is the possibility of cultural "interbreeding." If many "Bantu" groups of today have adopted certain aspects of Pygmy culture, as seems to be the case with music, despite their disdain for the Pygmies as social and intellectual inferiors, then who is to say that a similar dynamic might not have developed between Homo Sapiens and Homo Erectus during early stages of the Out of Africa migration?

I find it difficult, in fact, to completely rule out at least the possibility that some of the cultural transformations I've attributed to a major bottleneck, induced by Toba or some other disaster, could be due to the influence of traditions originating independently among archaic humans, who would certainly have been living in various regions of Asia at that time. If even one "modern" human of African origin managed to mate with a member of a Homo Erectus group, who is to say that such a union couldn't have produced the first "mongoloid" or first "australoid" or first "caucasoid"? And even if such a congress could not have resulted in "viable offspring," as many now suspect, it could have led to the sort of cultural symbiosis that might, under the right circumstances, have encouraged the "modern" humans to adopt some Erectus traditions, including musical traditions.

While I think it unlikely, it is in fact at least possible that a musical tradition such as, say, the unison/ iterative/ one-beat tradition, now so common among both Australians and Amerindians, could have originated among Homo Erectus peoples, to be adopted at some point by some Homo Sapiens group that could have passed it on intact to its descendants. Since such a transaction would have left no genetic trace, I don't see any way of testing such a hypothesis, but neither do I see any way of ruling it out. So at this point I have to admit that there is at least one viable alternative to the hypothesis I've been exploring -- and I find that possibility both intriguing and thought provoking.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

312. Alternatives

(. . . continued from previous post.)

In Chapter Six, of the book Folk Song Style and Culture (1968), titled "Song as a Measure of Culture," Alan Lomax unveiled a five-point scale of subsistence types as the basis for an evolutionary approach to the development of both culture generally and music in particular. The link he claimed to have discovered "between the norms of work and the norms of song" implied "that song style is a reflection and reinforcement of the way a culture gets its work done" (123), and that musical style will consequently change as work methods become more complex over time, from foraging to horticulture to increasingly sophisticated forms of agriculture. On this view of history, which Lomax was to vigorously promote and elaborate for many years thereafter, differences in musical style can be explained in terms of differences in subsistence type, each of which entails different methods of work. Therefore, in very general terms, as people work, thus do they sing.

Lomax's theory developed from a more basic assumption, shared by a great many anthropologists and ethnomusicologists even today, that music is an expression of culture and can be understood only in relation to its cultural context (a view that, as I see it, cannot be sustained, as it is inconsistent with abundant evidence that musical style can survive despite radical changes in cultural context). On this view, the musical gap I've noted could be explained as the result of a change in subsistence type that would, theoretically at least, have occurred in South Asia but apparently not Southeast Asia, Island Southeast Asia or Melanesia. I suppose such a change could be explained as a response to environmental factors unique to this region, or possibly to demographic factors due to rapid population expansion, according to the model suggested by Maju. As should be clear from my comments in Post 225, I have serious doubts about Lomax's theory, which was universally rejected many years ago, for reasons both good and bad, by anthropologists and ethnomusicologists alike -- but, again, it is an alternative to be considered.

The gap I've been pointing to in relation to my overview of the initial Out of Africa migration, centered on the distribution of P/B style, is in fact only one part of a much larger musical mystery, the almost total absence of traditional vocal polyphony of any kind throughout so much of Asia, from the Middle East through virtually all of village India, to Central Asia, almost all of China, Japan, Korea, and most (though certainly not all) of Southeast Asia, associated with the development of a remarkable type of virtuosic solo singing that Lomax called "elaborate style" (see Post 296). While the wide distribution of elaborate style can be understood in relation to the spread of various forms of "high culture" from the Neolithic to the modern era, the initial loss, in Asia, of polyphonic traditions stemming from our African roots (assuming the Out of Africa model), and commonly found in so many other parts of the world, must nevertheless be explained.

As far as I know, the only other musicologist to have systematically investigated this mystery is Joseph Jordania, who offers an explanation very different from mine in his remarkable book, Who Asked the First Question? The Origins of Human Choral Singing, Intelligence, Language and Speech.* Since Jordania does not subscribe to the Out of Africa model, but endorses the multiregional view instead, his overall orientation is very different from mine. There are some important similarities, nevertheless, including his conviction that our musical traditions ultimately have their origin in Africa (though among Homo Erectus rather than Homo Sapiens) and that these traditions were originally polyphonic:

According to the suggested model, initial forms of polyphonic singing (proto-polyphony) were distributed in all ancient populations of Homo Erectus (or more correctly, archaic Homo Sapiens). This ancient tradition of polyphony singing, with the new human cognition and the ability to ask questions was taken along on the long journey to different regions of the world (349).

As Jordania sees it, early humans lacked articulated speech, but made up for it through the development of musical abilities. Their displays of musical coordination had important survival value because they helped them ward off predators. As articulated speech slowly developed in various places, presumably via convergent evolution, their original musical aptitude withered, to become a kind of "vestigial organ":

After the advent of articulated speech musical (pitch) language lost its initial survival value, was marginalized and started disappearing. Early human musical abilities started to decline. The ancient tradition of choral singing started disappearing century by century and millennia by millennia. Musical activity, formerly an important part of social activity, also started to decline and became a field for professional activity. As a result of this decline, in some regions of the world the tradition of vocal polyphony is almost completely lost (349).The reason why "[t]he tradition of choral polyphonic singing has been lost among East Asian and Australian Aboriginal populations [while] still strongly present in European, Polynesian, Melanesian, and particularly – sub-Saharan African - populations" is due to "the shift to articulated speech among different populations in different epochs. Regions where vocal polyphony is absent (lost) must have shifted to articulated speech earlier. Regions where the tradition of vocal polyphony is still alive and active must have shifted to articulated speech much later" (350). Thus, for Jordania, we find no trace of choral polyphony in East Asia or Australia because articulated speech must have developed at a much earlier period there than in Europe, Oceania and Africa, and the advantages conferred by such an ability would have made coordinated musical activity no longer necessary.

Jordania's theory, while imaginative and interesting, is based on a long list of assumptions, most if not all of which are probably untestable. The only evidence he provides in support of his model is an apparent correlation between the distribution of traditional vocal polyphony and the worldwide distribution of stuttering. Since stuttering, for him, is associated with the relative novelty of articulated speech in the societies in which it occurs, a correlation between stuttering and polyphony would, in his view, support his theory that the development of articulated speech led to the decline of musical aptitude.

While I have the greatest respect for Jordania as an important authority on the polyphonic traditions of Europe (see Posts 119 et seq.), his theory associating an alleged convergent development of articulated speech independently in different parts of the world with the loss of vocal polyphony as a survival mechanism, piling one huge and untested assumption on top of another, seems extremely far fetched. What impresses me, nevertheless, is the fact that Jordania, almost alone among students of world music, has recognized the importance of this problem and at least made an attempt to deal with it. The fact that he was forced to go to such lengths to account for the extremely uneven distribution of vocal polyphony worldwide gives us an inkling into the difficulty of solving this perplexing enigma.

*Jordania's book was at one time freely available for Internet download, but that website has now disappeared. As I understand it, a new edition is currently in press and should be available for purchase soon.

*Jordania's book was at one time freely available for Internet download, but that website has now disappeared. As I understand it, a new edition is currently in press and should be available for purchase soon.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

311. Alternatives

Beginning way back in Post 225, I've been exploring a particular historical/ evolutionary scenario, starting with certain inferences about the nature -- and culture -- of our "most recent common ancestors," and proceeding with a series of increasingly speculative speculations centered on the adventures, misadventures, trials, tribulations and triumphs of their descendants, the Out of Africa migrants, as they and their progeny (allegedly) made their way through Asia along "the southern route," all the way to what is now New Guinea and Australia. It's important to remember that this particular attempt at historical reconstruction was made possible, first, by the musical evidence, which is in certain ways unique; and, second, by the use of the musical evidence to help establish a baseline, from which we were able to proceed step by step, in an orderly and logical manner. As I see it, two of the most glaring omissions in the anthropological and archaeological literature have been the neglect of both these areas: the neglect of musical style as an essential element of core culture, clearly on a par with language in importance, but far simpler and thus far more amenable to cross-cultural comparison; and the assumption that one could reconstruct important aspects of human history and/or evolution without first establishing a clear baseline from which to begin.

I have all along been referring to this overview as an "exploration," meaning that, as far as I'm concerned, it is tentative, incomplete and possibly incorrect -- but imo a useful exercise nevertheless. It also amounts, I would think, to a testable hypothesis, or set of hypotheses, with the ultimate tests most likely stemming from the field of population genetics, which is only now beginning to realize its enormous potential, and still has a long way to go. Nevertheless, I've been accused of being selective in my use of evidence and neglecting to consider alternative explanations, with the implication being that what I'm calling an exploration is in truth nothing more than a pet theory, or worse, a crackpot theory, which must be defended at all costs. I've denied that this is the case and have often asserted that I'd be happy to accept any alternative explanation that both accounted for the evidence and made sense. But at the same time I refused to drop my line of thought for side excursions to examine evidence that didn't seem to fit, and consider alternative explanations. Now that my overview is complete, it's time to do just that.

According to one of the most active commenters on this blog, Maju, the most up-to-date genetic evidence does not support the gap I see in South Asia, nor does it support the notion that there was ever a significant large-scale bottleneck or series of bottlenecks in South Asia, consistent with either the Toba eruption or any other major disaster, such as a Tsunami, drought, etc. that might have occurred during the Out of Africa expansion along the southern route. Maju has argued that the discontinuities between India and Southeast Asia that I've pointed to, clearly apparent in some of the phylogenetic trees and related maps, are either due to sloppy, simplistic research or represent methodological artifacts rather than logical inferences from the genetic evidence. As I see it, it's simply too soon to tell with any degree of confidence which of the many interpretations of the data are correct and to what extent future research with refined methods and expanded samples will either confirm or challenge the findings of any one group.

Assuming, however, that Maju's objections are in fact legitimate, then we must consider alternative scenarios that could explain the apparently inexplicable gap that exists in the cultural evidence, especially the musical gap, where we see no sign of the "African signature," either vocally or instrumentally, anywhere in South Asia and in fact anywhere from Yemen all the way to the eastern borders of India, and yet find it in abundance among a great many isolated indigenous groups to the east and southeast of India, including southeast Asia, island southeast Asia and Melanesia. Maju's explanation is based on a recent finding to the effect that the larger the population, the greater the degree of innovation, which for him means that a society with more opportunities for interaction among various members of its population is a society that is more likely to undergo change. And since there is in fact excellent evidence for a tremendous population expansion centered in South Asia shortly after the Out of Africa migration, that could explain the various cultural changes, including musical changes, that would have taken place there. I have grave doubts about this scenario, which strikes me as overly simplistic and not fully explanatory, but it's an example of an alternative hypothesis and certainly worth considering.

Another angle to consider is the series of extremely complex developments centered in South Asia from the earliest beginnings of the Neolithic to the rapid evolution of civilization(s), a dramatic series of events that transformed the entire region and would certainly have presented a challenge to the various indigenous peoples seeking to maintain age-old traditions in the face of enormous military, political and social pressure. While a great many tribal groups did in fact wind up as castes, under the thumb of more powerful groups who sought to control every aspect of their lives, a great many did apparently maintain their independence, largely by retiring to refuge areas, minding their own business and avoiding conflict wherever possible. There remains the question, however, of the degree to which they were able to remain fully independent, as was the case with so many "relic" peoples farther to the east, or whether there was a certain amount of encroachment in each and every case, over thousands of years, that could have led to a certain degree of cultural homogeneity, despite the isolation of so many of the Indian "tribals." One does get the impression, when one explores the various musics of so many Indian and Pakistani groups, of a certain uniformity of musical style and practice throughout the subcontinent, a somewhat disturbing phenomenon that is especially apparent in the "folk" music of the villages, which never seems to depart very far from the "classical" raga style cultivated by the upper castes. Whether the same sort of pressure to conform has been felt by the ostensibly more independent tribal groups is difficult to assess. But if that has been the case, then it's possible that the absence of any trace of P/B in India or Pakistan could be due to external pressures from more powerful groups, either in recent or ancient times, which could have wiped out just about all trace of more archaic cultural practices. Why such a thoroughgoing process of cultural assimilation would have occurred in South Asia and not Southeast or Island Southeast Asia isn't clear but again, such a possibility is worth considering.

(to be continued . . .)

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

310. Aftermath 25: Australia and New Guinea

(. . . continued from previous post.)

What's implied in my phylogenetic tree is that the traditional, highly interactive, musical style brought out of Africa by HMP (the "Hypothetical Migrant Population") could have been seriously disrupted due to some major population bottlenecks produced by a serious and wide-ranging disaster, centered roughly in South Asia, at a time when relatively small colonies of migrants would have been spread out over much of the Indian Ocean coast. Such an event could account for at least some of the major discontinuities we see when we examine the traditional musical styles of so many societies in various parts of the world today. My tree focuses on three distinctive proto-styles, B1, B2 and B3, that could have emerged from such an event, but there could have been some others as well -- my phylogeny may well be far from complete.

To understand how the distinctive, and actually quite remarkable "unison/ iterative/ one-beat" style of the Australian Aboriginals could have originated, we need to look first at its predecessor: B3. B3, or "Social Unison" can be seen as prototypical for a great many musical sub-styles now found largely in Oceania (including Australia), with possible relatives in Eastern and Southern Europe, and an important branch in the Americas. We can hypothesize either that B3 originated among a single, very small, group of disaster survivors probably living somewhere to the east of India, and then spread to other regions of Asia, Europe, Oceania and the Americas as the descendants of this population expanded in all directions over thousands of years; or, and probably more likely, that various versions of B3 arose more or less simultaneously among different groups living in roughly the same area, and spread in various directions as the descendants of those groups expanded.

What all such cases would have had in common would have been a serious disruption of social life resulting from the disaster. Since P/B is so dependent on the close and even intimate interaction of all participants, it's not difficult to see how such a style could have vanished in the face of serious adversity of a sort that could have pitted formerly cooperative families and individuals against one another in a desperate struggle for survival. After the dust cleared, and social life began to return to normality, efforts to revive ancestral traditions may well have been hampered by the disruption of the normal process of cultural transmission from one generation to the next. So it's not difficult to see how simpler musical traditions, such as the various versions of B3, could have emerged.

Among some groups, interlocked polyphonic vocalizing may have given way to simple leader-chorus alternation or, among others, social unison -- in some cases with the retention of polyphony in the form of parallel harmonies or drone effects, while in other cases the newly emergent society may have completely lost its ability to sing in harmony -- or alternatively, dismissed the harmonizing of neighboring groups as a crudely "primitive" practice to be avoided at all costs in favor of a more carefully controlled and constrained approach to solo singing, and/or the development of precisely synchronized unison vocalizing. (It's important to recognize that among many such groups unison is not merely due to an inability to harmonize, but that even incidental harmonizations are seen as mistakes to be avoided.)

It is on such a basis that we can see Australian Aboriginal style (B3a2), and it's close relatives in New Guinea and Island Melanesia, emerging. Not necessarily as a direct result of the same bottleneck that would appear to have produced the "Australoid" morphology, but as a development from it, i.e., as a development from the proto-style I've called B3. Since we do not currently find B3a2 among any South Asian tribal groups or, indeed, any musical traditions now known between India and East Indonesia (to the best of my knowledge), it's tempting to assume that B3a2 may have originated in the Sahul itself, possibly due to the population bottleneck that would have occurred when the first wave of Australoid males invaded, thousands of years after the initial "Negrito" settlement of that continent.

There is a problem with that scenario, however, due to the fact that B3a2 has a "sister" clade, B3a1, which turns out to be the dominant musical style for almost all of native North America, and much of Central and South America as well. The two substyles can sound very similar, especially when Australian Aboriginal singing is compared with Plains Indian singing, an especially close match in melodic type along with everything else. The principal difference is that Australians tend to emphasize relatively narrow intervals in their melodies, whereas Amerindians prefer wide intervals, such as thirds, fourths and fifths. Harsh, tense-voiced unison singing, with frequent iteration of the same note, accompanied by a single, repeated beat on either drums or rattles (Indians) or percussion sticks (Australians) tends to be the rule in both traditions. There are important differences as well, especially since drums of any kind appear to be unknown in Australia, while extremely important in the Americas. And there is no equivalent of the Didgeridoo in the Americas.

Do both traditions stem from a common root? Or are the many resemblances coincidental? If they do in fact stem from a common root, which seems likely, then it's necessary to place the origin of this style early enough to account for what would have to have been a very early divergence between the ancestors of the two groups, which are, of course (and this adds to the problematic aspect of this association), very different morphologically. Genetically, however, there does seem to be a link, since the Y chromosome C haplogroup is in fact found in all the Asiatic/Oceanic B3 groups in my musical tree. And, as German Dziebel has recently reminded me, a Cantometric factor analysis done by Alan Lomax back in 1980 united many Amerindian groups with Australian Aboriginals as part of what he termed a Circum-Pacific family. According to Lomax, "In East and Southeast Asia the rise of high Chinese, Indo-Chinese, Malaysian and Polynesian high culture obscures a tradition that seems to have once stretched uninterruptedly from Siberia south to Australia. The Circum-Pacific model still shapes the performances of aboriginal Australia, much of Melanesia and parts of backwoods Malaysia . . . ("Factors of Musical Style," in Theory and Practice: Essays Presented to Gene Weltfish, ed. S. Diamond, p. 37). If Lomax is right, then North America and Australia could be regarded as enormous refuge areas, populated during a period when more advanced Neolithic societies were beginning to expand, pushing their hunter-gatherer neighbors increasingly into peripheral areas.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

309. Aftermath 24: Australia and New Guinea

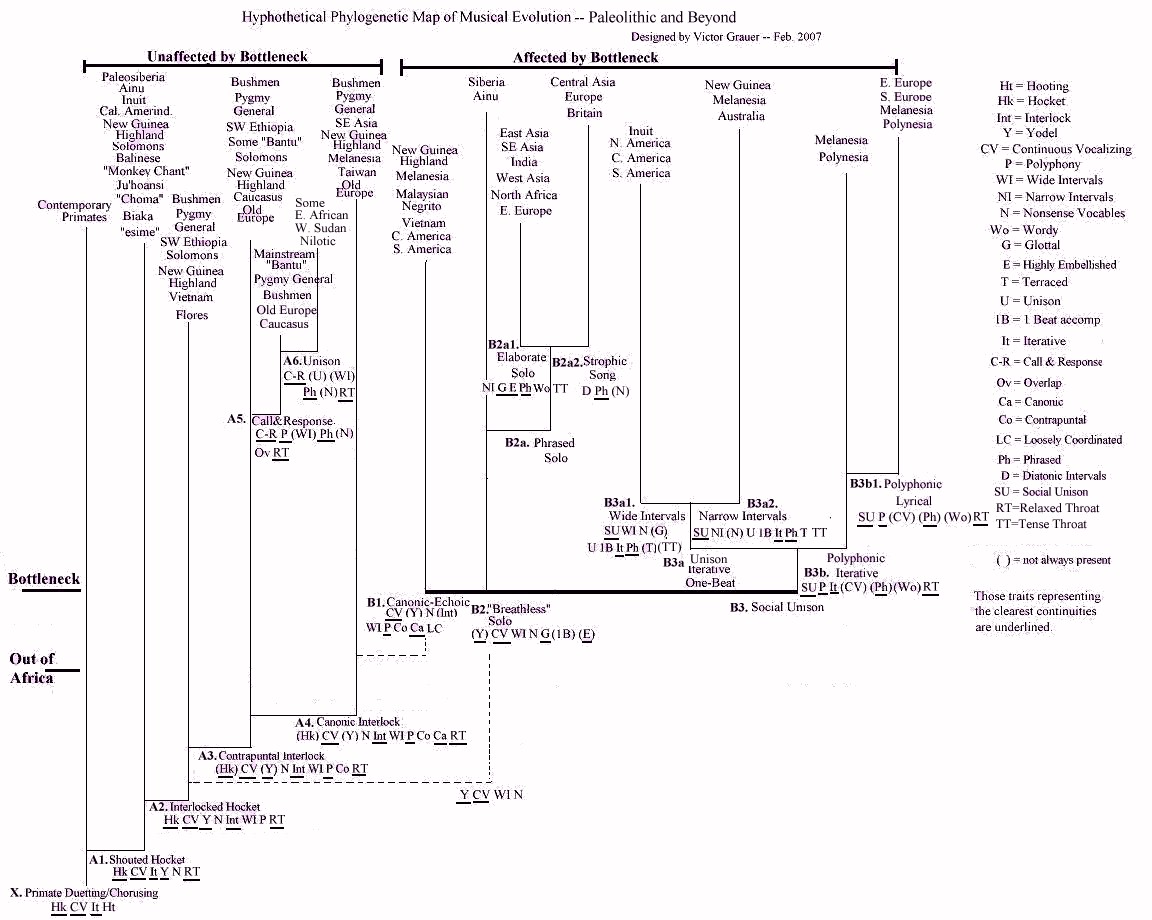

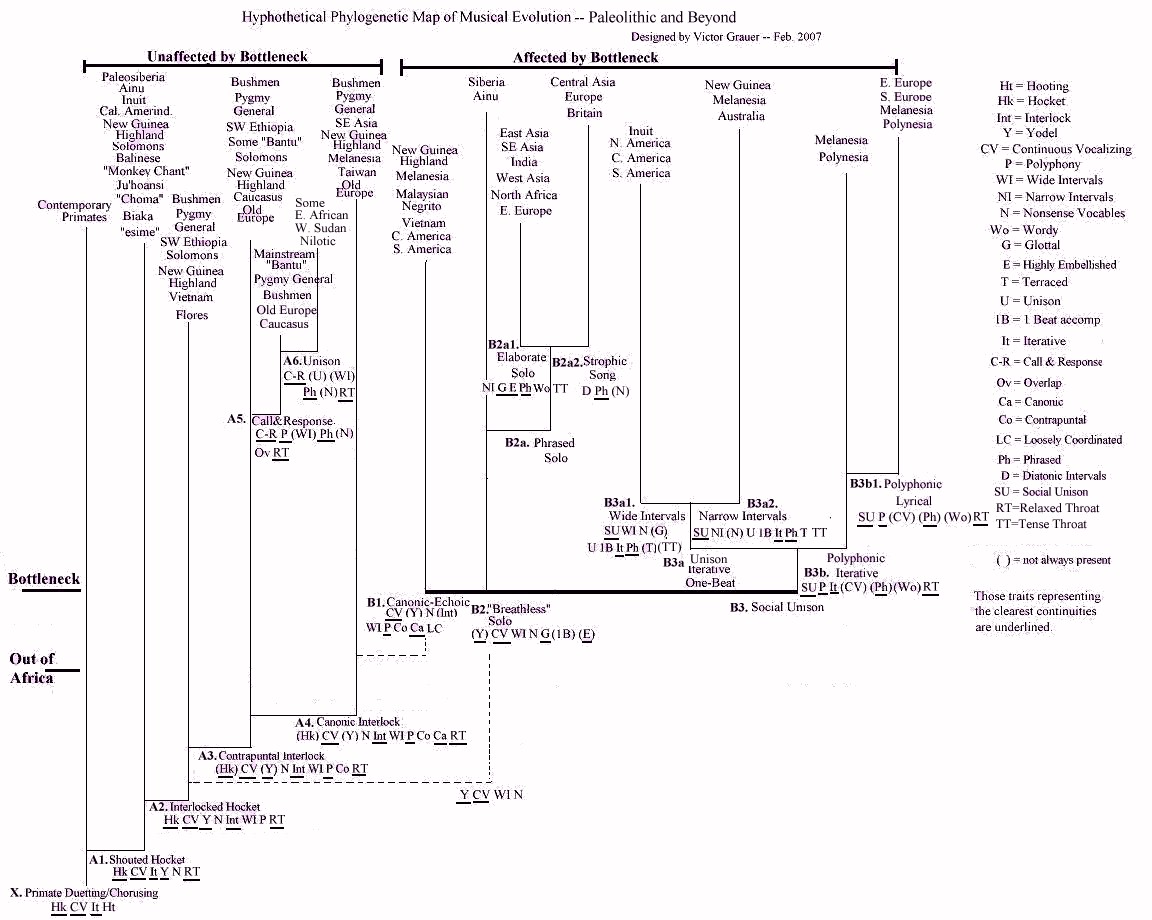

To get a better handle on the problem posed by the music of the Australian Aboriginals, let's take another look at the phylogenetic tree I presented all the way back in Post number 12:

While the thinking behind this tree was, and still is, subjective, speculative and tentative, it remains useful, in my opinion, as a means of helping us visualize certain possibilities. (It's important, also, to understand that this is primarily a representation of vocal style -- instrumental music is represented only to the extent that it serves as an accompaniment to vocalizing. While instrumental music can be equally important, it is much more difficult to assess on a comparative basis.) While it might look at first glance like a conventional phylogeny, in which each new branch represents a progressively more complex or "creative" developmental stage, it actually represents something very different. Because, at heart, my approach to musical "evolution," and, to some degree, cultural evolution generally, is based on the following principle, as expressed in my essay, "Echoes of our Forgotten Ancestors" -- what I call the "principle of sociocultural inertia": a tendency on the part of any human group to retain the most deeply ingrained and highly valued elements of its lifestyle until acted upon by some outside force (10).

While the thinking behind this tree was, and still is, subjective, speculative and tentative, it remains useful, in my opinion, as a means of helping us visualize certain possibilities. (It's important, also, to understand that this is primarily a representation of vocal style -- instrumental music is represented only to the extent that it serves as an accompaniment to vocalizing. While instrumental music can be equally important, it is much more difficult to assess on a comparative basis.) While it might look at first glance like a conventional phylogeny, in which each new branch represents a progressively more complex or "creative" developmental stage, it actually represents something very different. Because, at heart, my approach to musical "evolution," and, to some degree, cultural evolution generally, is based on the following principle, as expressed in my essay, "Echoes of our Forgotten Ancestors" -- what I call the "principle of sociocultural inertia": a tendency on the part of any human group to retain the most deeply ingrained and highly valued elements of its lifestyle until acted upon by some outside force (10).

If I could ever be accused of having a "pet theory" that I would go to great lengths to defend, it just might be encapsulated in this principle. And it should go without saying that I regard music, or at least musical style (for want of a better word), as among the most "deeply ingrained and highly valued elements" of human culture, especially so among those peoples who have not yet reduced it to a specialized form of entertainment ("Pop" or "Rock") or enlightenment ("Classical" or "Sacred" or, again, "Rock") given over to the hands of professionals.

In accord with this principle, most (though probably not all) the branchings in this tree can be understood, not as stages in a developmental process, but as the result of some sort of breakdown, due to an encounter with some "outside force," such as the encroachment of a more powerful and aggressive society, or a natural catastrophe (such as the Toba explosion, but also a Tsunami, earthquake, famine, drought, etc.) of the sort that can decimate a population and turn life upside down for the survivors. By analogy with the genetic concept of a "population bottleneck," such encounters can result in "cultural bottlenecks," where certain traditions may be lost and replaced by something different, due to resulting "founder effects" -- either somewhat different or completely different, depending on factors that are in many cases impossible to predict. I'll add that very often population bottlenecks, of the sort studied by population geneticists, can easily result in cultural bottlenecks, so cultural (and of course musical) "founder effects" can often be correlated with genetic ones. For more on the phylogenetic tree generally, see Post 12 et seq.

If we look for the word "Australia" on this tree, we will find it in only one place, just above the musical "clade" (branch) labeled B3a2. This clade stems from a deeper one, B3a, labeled "Unison/ Iterative/ One-beat." B3a, in turn, stems from B3, "Social Unison." You'll note that there is nothing beneath B3, no deeper clade which might have given rise to it. Instead, we see a thick horizontal line linking it with its sister clades, B1 and B2. If you now look all the way to the left, you'll see, in the margin, the word "Bottleneck." And if you look directly above the thick horizontal line, you'll see "Affected by Bottleneck." What we see in superhaplogroups B1, B2 and B3 is an attempt on my part to perform an educated guess as to what the musical effects of a major bottleneck event, such as the Toba eruption, or a Tsunami, etc., might have been. And since such an event would have been both devastating and relatively abrupt, it's not difficult to conclude that the effects would also have been both devastating and abrupt -- or in the words of the evolutionists, "saltational" (i.e., involving a sudden leap rather than a gradual transformation).

I placed nothing beneath B3 because there is little or nothing in SubSaharan African music that could be seen as a supporting "branch" for this particular style. Most SSAfrican music, both vocal and instrumental, is interactive, based either on closely interlocking, "contrapuntal" parts, as with P/B and its variants, or the well known "call & response" so characteristic of Bantu and African-American music. Much is also polyphonic, ranging from free counterpoint, to canon, to singing in parallel harmonies in either 4ths and 5ths or 3rds. We do find unison singing among certain African groups, but this practice appears to have developed relatively late.

As I've already argued, many posts ago, the type of vocalizing most likely to have been practiced by the original Out of Africa migrants (HMP) would have been P/B or some near variant, in other words music that is highly interactive, closely interlocked and polyphonic. B3, on the other hand, is called "Social Unison" because all the singers sing together more or less in lock step rhythmically throughout, with little or no leader-chorus interchange, a practice almost unheard of in SSAfrica. There are two B3 branches, one unison (B3a), the other polyphonic (B3b), and since polyphony is so common in Africa it's possible that B3b preceded B3a, which may have lost its polyphony as the result of a subsequent bottleneck event. It's also possible, as implied by the diagram, that both branches represent independent responses to the major bottleneck, by at least two different groups.

(to be continued . . . )

Sunday, February 7, 2010

308. Aftermath 23: Australia and New Guinea

Even if we assume that the hypothetical scenario I've been presenting is more or less on-track, a particularly challenging problem remains: the origin of the remarkable musical style that, as far as I've been able to determine, is characteristic of just about every Australian Aboriginal group throughout all regions of the continent. While there do seem to be some intriguing similarities between the dance styles of the Chenchu and Australian Aboriginals, as noted in Post 299, I've never been able to find any musical practice anywhere in South Asia that resembles the "unison/ iterative/ one-beat" style of the Australians.

*From the Mumonkan: The Sixth Patriarch was pursued by the monk Myõ as far as Taiyu Mountain. The patriarch, seeing Myõ coming, laid the robe and bowl on a rock and said, "This robe represents the faith; it should not be fought over. If you want to take it away, take it now." Myõ tried to move it, but it was as heavy as a mountain and would not budge. Faltering and trembling, he cried out, "I came for the Dharma, not for the robe."

I've been accused of going too far, at times, to justify my "pet theory" of musical evolution, and my attempt to account for Australian Aboriginal music in terms of some sort of bottleneck event, possibly due to the Toba eruption, is seen as a perfect example of how I am forced to go to unlikely extremes in order to make my theory work. No matter how many times I repeat myself, it seems to do no good, but just for the record: I do not have a theory of musical evolution, or evolution generally, either "pet" or otherwise. I am, very simply, trying to make sense of what happened in early human history, in terms of the various types of evidence available to me. To that end, I find it convenient to explore certain possibilities, in the form of testable hypotheses, which I then try, as best I can, to put to the test.

Since by far the strongest and most promising evidence comes from the realm of population genetics, and the strongest and most promising hypothesis is the "Out of Africa" model, my principal effort for the last several years has been to explore as fully as I can what that model implies for both musical and cultural evolution -- to determine whether what I know or think I know about the musical picture especially is or is not consistent with what I am learning about the picture currently being painted by the intrepid geneticists. If I can't get the pictures to coordinate into some sort of focus, then I will be forced to consider some other alternative. And that will be fine with me. If I were in it for the robe and bowl,* the course of my entire life would have been very different, I can assure you. I am here strictly and exclusively for the Dharma. (Though a bowl full of rice -- in the form of a grant -- would, from time to time, be welcome.)

If there is a "pet theory" to be justified by the bottleneck I have in mind, it is not a theory of music, but the "Out of Africa" theory itself. Because the existence of Australian Aboriginal "unison/ iterative/ one-beat" style is, on its face, very difficult to explain as an "evolutionary development" from anything remotely African. And if we might want to explain it away as an "independent invention," we would still be left with the problem of why such an invention was needed in the first place, if the ancestors of the Australians already had a perfectly viable musical tradition, with roots, like the Australians themselves, in Africa. On its face, the profound difference between this style and the P/B style I've associated with our HBP ancestors, and the HMP migrants, is so great as to be more consistent with the very different multi-regional model.

According to the multi-regionalists, the great diversity we see in the world of today, genetic, morphological and cultural is due to the fact that modern humans developed more or less independently in different regions of the world, so that things we have in common, like language, music, ritual, myth, marriage customs, kinship systems, religion, etc., must be the product of convergent evolution, i.e., some sort of "destiny," based on certain universal properties of the human mind that cause it to develop along certain lines and not others. A somewhat softened version of this model claims that many of these similarities must be due to various processes of genetic and cultural interchange due to the continual migration of various peoples throughout the world over millions of years. And any differences, such as the many differences between P/B and "Unison/ Iterative/ One-beat," wouldn't need explaining, since they would be due to the fact that these two styles arose under completely different circumstances, in completely different regions of the world. Any version I've ever heard of the multi-regional model makes little sense to me, while the Out of Africa model makes a great deal of sense. So, if the music of the Australian Aborigines can't somehow be accounted for by some version of Out of Africa, then I have to admit I'm stumped and will need to start over.

(to be continued . . . )

*From the Mumonkan: The Sixth Patriarch was pursued by the monk Myõ as far as Taiyu Mountain. The patriarch, seeing Myõ coming, laid the robe and bowl on a rock and said, "This robe represents the faith; it should not be fought over. If you want to take it away, take it now." Myõ tried to move it, but it was as heavy as a mountain and would not budge. Faltering and trembling, he cried out, "I came for the Dharma, not for the robe."

Saturday, February 6, 2010

307. Aftermath 22: Australia and New Guinea

17. If my scenario is correct, we should expect to find the following population types in what was formerly the Sahul:

[Added Feb. 7: The above sentence should be rephrased as follows: "If my scenario is correct, then the current situation in the former Sahul could be described in the following terms:"]

1. in Australia, Aborigines with Australoid morphology and Aboriginal hunter-gatherer culture, speaking, for the most part, a Pama-Nyungan language ; 2. in New Guinea, descendants of the original "Negrito" settlers, possibly with a degree of Australoid intermixture, now surviving mostly in the highlands, but also along portions of the coast, living as foragers and part-time horticulturalists -- speaking various "Papuan" languages, though in some cases -- especially along the coast -- Austronesian languages, and retaining at least some of their original African traditions; 3. in New Guinea, descendants of Australian Aborigines formerly based on the New Guinea coast, now living for the most part in the highlands as forager/horticulturalists, possibly intermixed with population 2, both biologically and culturally -- also speaking "Papuan" or in some cases Austronesian languages; 4. relatively recent Austronesian immigrants, speaking Austronesian languages, and inhabiting, for the most part, the northern coastal and lowland areas of New Guinea; practicing an essentially Neolithic, agriculture-oriented culture, with roots in Southeast Asia and strong connections with Polynesia -- but in certain respects also influenced by neighboring Papuan speakers, and in certain cases even speaking Papuan languages.

[Click on the image to enlarge.] For example, the cluster labeled "2a" is a mixture of New Guinea highland and coastal groups, along with a single representative of the Nasioi speakers of Bougainville, in the Solomon Islands. Since Papuan (i.e., non-Austronesian) speakers can be found in both the highlands and the coast, and since Nasioi is a Papuan language, this cluster could be seen, hypothetically, as representative of population group 2, as defined above, i.e., descendants of the original "Negrito" settlers. Since all but one of the groups represented in cluster "1b" are from the highlands, and thus in all likelihood also Papuan speakers, this cluster could also be assigned to group 2. Clusters "1c" and "1d," on the other hand, represent a mix of New Guinea highlanders and Australians, suggesting that the New Guineans in these samples might have originated in group 3, i.e., highland populations in New Guinea formerly centered along the coast, who are not "Negrito" descendants, but originated as Australoid immigrants. There are in addition several unhighlighted clusters (in block 1 only) representing purely Australian groups, which can unproblematically be assigned to population group 1, i.e., Australian Aborigines descended from the original Australoid immigrants. Finally, cluster "1a," a mix of Polynesian and New Guinean coastal populations, most likely belong to group 4, i.e., Austronesian speaking Neolithic farmers, living for the most part along the northern coast of New Guinea, but biologically and culturally most closely associated with Southeast Asia and Polynesia. The above picture, in addition to being highly speculative, is clouded by the authors' failure to identify the specific groups sampled (with the exception of the Nasioi), and also the tendency of Melanesian peoples generally to borrow cultural elements from one another, including not only tools and farming methods, but also rituals, musical instruments and even, on occasion, specific musical practices, at least to some extent. So clearly much more research will be necessary before the hypothesis in question can be adequately tested.

18. The phylogenetic tree I presented in Post 301, (from the 2003 paper by Max Ingman and Ulf Gyllensten, Mitochondrial Genome Variation and Evolutionary History of Australian and New Guinean Aborigines [11]), appears, in certain respects, to reflect the fourfold population structure outlined above*:

[Click on the image to enlarge.] For example, the cluster labeled "2a" is a mixture of New Guinea highland and coastal groups, along with a single representative of the Nasioi speakers of Bougainville, in the Solomon Islands. Since Papuan (i.e., non-Austronesian) speakers can be found in both the highlands and the coast, and since Nasioi is a Papuan language, this cluster could be seen, hypothetically, as representative of population group 2, as defined above, i.e., descendants of the original "Negrito" settlers. Since all but one of the groups represented in cluster "1b" are from the highlands, and thus in all likelihood also Papuan speakers, this cluster could also be assigned to group 2. Clusters "1c" and "1d," on the other hand, represent a mix of New Guinea highlanders and Australians, suggesting that the New Guineans in these samples might have originated in group 3, i.e., highland populations in New Guinea formerly centered along the coast, who are not "Negrito" descendants, but originated as Australoid immigrants. There are in addition several unhighlighted clusters (in block 1 only) representing purely Australian groups, which can unproblematically be assigned to population group 1, i.e., Australian Aborigines descended from the original Australoid immigrants. Finally, cluster "1a," a mix of Polynesian and New Guinean coastal populations, most likely belong to group 4, i.e., Austronesian speaking Neolithic farmers, living for the most part along the northern coast of New Guinea, but biologically and culturally most closely associated with Southeast Asia and Polynesia. The above picture, in addition to being highly speculative, is clouded by the authors' failure to identify the specific groups sampled (with the exception of the Nasioi), and also the tendency of Melanesian peoples generally to borrow cultural elements from one another, including not only tools and farming methods, but also rituals, musical instruments and even, on occasion, specific musical practices, at least to some extent. So clearly much more research will be necessary before the hypothesis in question can be adequately tested.

19. In 2007, on the basis of Cantometric evidence, supplemented by a renewed survey of available recordings and field studies, I put together a report entitled "The Musical Affinities of Some Melanesian Groups." Interestingly, my study produced musical "families" closely correlated with the grouping presented above. The first such family consisted of "Groups Exhibiting Strongest Association with African Pygmy/Bushmen style," i.e., those groups most closely associated musically with the culture of the original Out of Africa migrants (HMC). A second family was characterized by a variant of P/B style that I've called "canonic-echoic." In both cases, all but one of the 12 groups from New Guinea were located in the highlands, and all were Papuan speakers, strongly suggesting membership in population group 2, as defined above. Another style family was "Groups Exhibiting Strongest Association with Indigenous Australia – Unison Singing with 1-beat Accompaniment." Interestingly, only one group from island Melanesia was represented here, along with a mix of 5 New Guinea groups from both the highlands and coastal areas, suggesting membership in group 3. The last category, corresponding to group 4, was "Groups Exhibiting Strongest Association with Western Polynesia," with typically Polynesian characteristics, such as "polyphonic group vocalizing in either rhythmic unison . . . or some form of simple antiphony, with good to excellent tonal blend, medium interval width, wordy . . ." In New Guinea, these were mostly coastal groups, with only one highland group represented -- along with the inhabitants of the Torres Straits, whose culture has been described as closer to Melanesia than Australia, and who may well have been exposed to Austronesian influence. Again, this picture may be distorted by the tendency of some of these groups to borrow rituals, instruments and in some cases even particular songs from one another. Nevertheless, I find the parallels between the historical scenario, the genetic evidence and the musical evidence to be compelling and definitely worthy of further investigation.

*As you may recall, this tree is a bit unusual, as it's based on the mtDNA coding region rather than the noncoding "neutral markers" of the "D-loop," which has usually been the focus of this sort of research in the past. For this reason, the authors chose to forego the usual haplogroup terminology (L, M, N, etc.), which could be misleading. Nevertheless, the clades grouped under the labels "1" and "2" are to be understood as essentially equivalent to mtDNA superhaplogroups "N" and "M" respectively.

*As you may recall, this tree is a bit unusual, as it's based on the mtDNA coding region rather than the noncoding "neutral markers" of the "D-loop," which has usually been the focus of this sort of research in the past. For this reason, the authors chose to forego the usual haplogroup terminology (L, M, N, etc.), which could be misleading. Nevertheless, the clades grouped under the labels "1" and "2" are to be understood as essentially equivalent to mtDNA superhaplogroups "N" and "M" respectively.

Thursday, February 4, 2010

306. Aftermath 21: Australia and New Guinea

12. Monash University has a very interesting website that provides detailed information on sea levels from roughly 100,000 ya to the present, coupled with a map of the Sahul. It's interactive, so you can run your mouse over the timeline to see where sea levels were at any given time and how they affected what is now New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania. As we can see from the map, sea level rose very rapidly from about 25,000 ya to roughly 7,400 ya. when it reached more or less the same level it has today. Extrapolating backward, we can imagine the situation as it may have existed, according to the hypothesis I'm exploring, once the three regions were completely separated: 1. Australia would by then have been largely populated by Australoid peoples similar to those who now form the great majority of Australian aboriginals; 2. the Queensland tropical forest could have served as a refuge area for a small segment of the original "Negrito" population; 3. Tasmania, now an island, could have been another refuge for descendants of the same original group; 4. New Guinea would have been populated largely by refugees, descended from the original Sahul settlers, living mostly in the mountains, surrounded by Australoid "invaders" living along the coast.

The huge yellow region is where Pama-Nyungan languages are spoken, while the much smaller, multi-colored region to the north contains just about every other language family on the continent. Significantly, these northern languages are located just to the south of where an enormous land bridge once connected Australia and New Guinea (see map on Post 297). It's tempting to speculate that this northern region might once have served as a refuge area for groups of besieged "Negritos," possibly a jumping-off point for the voyage north. If the invaders ultimately captured their women, taking them as wives, it's possible that their languages might have survived the destruction of the rest of their culture.

13. At some point, a form of agriculture characterized by simple gardening (horticulture) develops in New Guinea, either among the highland "Negritos" or the coastal "Australoids," and spreads rapidly throughout the island. Australia, now largely or completely separated from New Guinea, is unaffected by this development and the Australians remain hunter-gatherers right up until first contact with the West.

14. Because Australia is largely flat terrain and also because of the remarkable ability of Australian aborigines to walk great distances, the entire continent tends toward a remarkable homogeneity, both morphologically and culturally. For example, a single language family, Pama-Nyungan, dominates almost the entirety of the continent, in contrast to New Guinea, which currently harbors over 1,000 languages divided into "about three dozen language families and close to the same number of language isolates" (The Languages of New Guinea, William Foley). The very different distribution pattern for language families in Australia is clearly visible in the following map (from the Wikipedia article, Indigenous Australian Languages).

The huge yellow region is where Pama-Nyungan languages are spoken, while the much smaller, multi-colored region to the north contains just about every other language family on the continent. Significantly, these northern languages are located just to the south of where an enormous land bridge once connected Australia and New Guinea (see map on Post 297). It's tempting to speculate that this northern region might once have served as a refuge area for groups of besieged "Negritos," possibly a jumping-off point for the voyage north. If the invaders ultimately captured their women, taking them as wives, it's possible that their languages might have survived the destruction of the rest of their culture.

15. The striking difference between the linguistic pictures for the two islands is paralleled in the realm of music, with New Guinea currently harboring a variety of different vocal styles, with a wide range of different polyphonic types, some with strong African echoes, and a large number of different instruments and instrumental ensembles, while native Australian vocalizing, almost exclusively monophonic and highly iterative, is remarkably homogeneous stylistically, with only a very few relatively simple instruments, aside from the Didgeridoo, which is rarely performed in ensembles of any kind. It's important to recognize, however, that within the very broad limits of the style I've called "unison/iterative/one-beat" there is considerable diversity among various Australian groups, and also a very impressive degree of subtlety, rhythmic intricacy and structural elaboration, often coordinated with some of the most remarkable poetry and dancing to be found anywhere in the world. When we couple this with some of the most complex and intellectually challenging ritual, mythical, and genealogical traditions to be found anywhere in the world, along with equally remarkable visual art traditions, which even today can challenge the finest examples of Western art, it should be clear that when I characterize Australia as culturally "homogenous" this should not be construed as implying that these traditions are in any way simplistic or inferior. I'll have more to say about the music of Australia and New Guinea in future posts.

16. The next important event in the history of this region is the advent of the so-called "Austronesians," who are thought to have migrated to various points in New Guinea and Island Melanesia anywhere from 6,000 to roughly 4,000 years ago. The origin and early migration routes of the Austronesians remain a much-debated mystery, which need not concern us here. For some reason there is little if any evidence that any Austronesians ever landed anywhere in Australia, possibly due to the protective function of the Great Barrier Reef. However, they did land in New Guinea, where a great many Austronesian languages are spoken today, though almost exclusively in certain lowland areas, along the northern coast. Apparently, the newly arrived Austronesians displaced the New Guinea natives living along the coast, with results that are complex and only partly understood even today. In some cases it would seem as though the native populations remained put, but adopted Austronesian languages and also farming techniques. In other cases, it's almost certain that at least some groups took to the highlands, which once again would have served as a refuge area. As far as the scenario I'm developing is concerned, the "native" populations along the coast would at that time have been largely Australoid groups (see paragraph 11 in Post 305), while those inhabiting the highland regions would have been the descendants of the original "Negrito" settlers. With the advent of the Austronesians, therefore, and the retreat into the highlands of at least some of the Australoid groups, the highlands would have come to harbor a mixed population, partly of "Negrito" origin (though by now probably for the most part no longer Pygmoid) and partly of Australoid origin. Since these groups would have formerly, according to my scenario, been bitter enemies, it's not difficult to see how the endemic warfare we now see in the New Guinea highlands could have originated at this point.

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

305. Aftermath 20: Australia and New Guinea

(. . . continued from previous post.)

10. We can now extrapolate backward to speculate on how the arrival of these strangers could have led to the conditions we now see. And the first thing to consider is the fact that, in order to produce the largely Australoid population of today, the immigrants would have to have mated with the "native" women, probably forcibly at first, and at the same time largely either killed, displaced or enslaved the native men, wherever they encountered them. This would explain the "different histories" of males and females we see in at least some of the genetic evidence, as reported in Redd et al. The mtDNA picture would not reflect the presence of men from a completely different population, but the Y chromosome evidence would -- and that does seem to be the case. Over time, as the more aggressive and belligerent newcomers expanded throughout the continent, the original inhabitants would have done what so many relatively non-aggressive, non-competitive, non-violent peoples have done throughout history -- retired to easily defended or undesirable refuge areas. This would explain the special status of Tasmania [8], which could have served as a last stand for some of the natives as they retreated southeast to the point farthest away from the most likely point where the newcomers would have arrived, the northwest. And since Tasmania was originally a kind of peninsula with a fairly narrow land bridge, that might have worked for them as a last line of defense until the sea level rose and they became completely isolated on the island .

11. Since Australia is relatively flat and easily traversed, the original inhabitants would not have had much of a chance of survival, but could easily have been hunted down and slaughtered or enslaved, with their women appropriated for the usual reasons. Northeast Queensland contains a tropical forest, which was until recently, according to Birdsell's research, the home of a few small groups of Pygmies [2], who may have originally retreated to this area as a refuge, possibly many thousands of years ago. (For a summary of the controversy relating to the status of Australian Pygmies, see The Sydney Line.) But the most obvious refuge area would have been to the north, in what is now New Guinea, and it is the highlands of New Guinea that we can posit as the most likely refuge area for the newly victimized natives. If the newcomers arrived while New Guinea was still attached to Australia, they would have made their way north by land, but if the sea had already separated the two regions, they could still have retreated in crude boats or rafts, at least while the distance was not too great. The immigrants would have followed them, and could at that time have taken over the New Guinea coast, while the natives retreated into the hills.

(to be continued . . . )

Monday, February 1, 2010

304. Aftermath 19: Australia and New Guinea

( . . . continued from previous post.)

4. We must now return to an earlier era, prior to the settling of the Sahul, when colonies of Out of Africa migrants would have been strewn across the Indian Ocean coast, from the Indus Delta all the way to what is now Myanmar, Thailand, the Malay Peninsula and possibly beyond. Since progress along this coast is generally thought to have been rapid, possibly speeded by the use of rafts or boats, the various populations would have resembled one another in many respects, most likely with an African, if not actually Negrito, morphology and a culture still steeped in the traditions of HMC. I've already written of the necessity for some sort of "fudge" factor (along the lines of Alan Guth's Cosmic Inflation) to reconcile the basic Out of Africa model with the gap we now see in the form of a cultural and genetic discontinuity between the Horn of Africa and greater Southeast Asia (including the Sahul), a gap centered in South Asia. To account for this gap, as I've already argued, we are almost forced to posit a major population bottleneck (or series of bottlenecks) in this region, possibly due to the Toba eruption, at a very early stage of the OoA migration.

5. As a result of the precipitating event, the population of many if not all groups in South Asia and to some extent neighboring Southeast Asia, would have been drastically reduced, to the point that many lineages might not have survived at all, especially those in India. And population bottlenecks produced by such an event could have led to founder effects leading to the emergence, especially in the region to the east of India, of new and distinctive morphologies, which we could refer to as "proto-Mongoloid," "proto-Caucasoid" and "proto-Australoid." If there is, indeed, a relation between Paleosiberians, Mongols, Chinese, etc., such an event would provide us with a reasonable explanation for that relationship, which would have to have been based on a very early founding event, prior to the divergence of these groups from one another. Similarly, if there is more than an accidental relationship between the morphology of the Ainu and European "Caucasoids," such a founding event, at such an early period, and in that particular region, could explain it. Since Australoid morphology is much less far flung, there is less reason to argue that it too must have originated with the same event, and indeed it's possible that this very distinctive type might have emerged as the result of a more localized bottleneck event at some later date. Nevertheless, it seems reasonably safe to assume that Australoid morphology might well have originated in the same disastrous event as that which most likely produced the others.*

6. If Australoid peoples originated to the east of India, some groups could have migrated toward the west and south, where we find so many now (see Oppenheimer's The Real Eve for his theory of how India could have been repopulated in the wake of Toba), while others, or perhaps only one such group, could have slowly migrated east as well. If we can associate this population with Y chromosome haplogroup C*, as suggested by Redd et al [5], we can follow their progress across Southeast Asia, down to Island Southeast Asia and, finally, to either the southern Sahul or Australia, depending on the timing of their arrival.+ It is much too early, however, to claim a clear genetic association (or lack thereof) between Indian and Australian Australoids. However, it is unreasonable, as I see it, to insist that this very clear morphological association is some sort of illusion, simply because all the genetic i's and t's have not yet been dotted and crossed.

7. The most promising clue offered by the Redd et al study [5] is the significant difference they found between the histories of males and females in Australia. The mitochondrial phylogenies for the female line are all consistent with an early migration to the Sahul in the immediate wake of the Out of Africa migration, and little significant change in the population makeup since then, aside from what one might expect from differences produced by drift once New Guinea and Australia had become separated (roughly 10,000 years ago). It is partly due to this deceptively clear picture that Birdsell's "trihybrid" theory has been rejected in favor of the notion that the Sahul was populated by only one single immigration event. But this is a picture of the female line only. When we add the very different sort of evidence for the male line, as formulated by Redd et al, a very different picture of Australian/ New Guinean history emerges.

8. On the basis of this relatively new (though admittedly debatable) evidence, it's possible to suggest a scenario somewhat different from either that of Birdsell or his detractors. Thus, after the initial migration involving "gracile" or perhaps even "Negrito" types exclusively, with a relatively pacifistic HMC culture, we can posit another migration, occurring many thousands of years later, of Australoid hunter-gatherers with a very different, more aggressive and combative, post-bottleneck, culture. To be consistent with the genetic evidence, at least as it currently presents itself, the new immigrants would have to have been either exclusively or mostly male. It's very difficult to speculate as to when this event could have taken place. According to Redd et al,

The divergence times reported here correspond with a series of changes in the Australian anthropological record between 5,000 years ago and 3,000 years ago, including the introduction of the dingo [24]; the spread of the Australian Small Tool tradition [25]; the appearance of plant-processing technologies, especially complex detoxification of cycads [26]; and the expansion of the Pama-Nyungan language over seven-eighths of Australia [27]. Although there is no consensus among anthropologists, the former three changes may have links to India, perhaps the most relevant of which is the introduction of the dingo, whose ocean transit was almost certainly on board a boat. In addition, Dixon [28] noted some similarities between Dravidian languages of southern India and Pama-Nyungan languages of Australia.While this argument makes sense, it's not definitive, so there's no point in pinning ourselves down to the mid-Holocene immigration (or invasion) date suggested above. Regardless, the notion that an aggressive, largely or completely male group with an Australoid morphology arrived in Sahul/Australia to confront a largely non-aggressive, non-violent population already established in the most favorable places, could go a long way in accounting for the picture we now see in both Australia and New Guinea.

(to be continued . . . )

*Again, I must emphasize that I am not referring to "racial" differences, but morphological ones. There is no such thing as a science of "race" (partly because no one really knows how to define that term as anything other than a social construct) but there is certainly a science of comparative morphology, a far less ambitious, and more clearly circumscribed, mode of anthropological research, which, because of its questionable history, is often confused with "racial science."

+The picture for Australia was "corrected" by Hudjashov et al [14], who discovered two new C haplogroups in Australia, C4a and C4b. But they don't say whether or not this directly contradicts what Redd et al claim to have found, i.e., a significant presence of C* in Australia, and a 2% presence in India, among tribal groups likely to have Australoid morphology. In fact the Hudjashov group's discussion of the Y haplogroups is confined to only a single paragraph and is incomplete and also vague. They claim their evidence is inconsistent with Huxley, who lived in the 19th century, but make no reference to Redd et al, whose study dates from only a few years prior to theirs. Regardless of their discoveries regarding C4a and C4b, the real question is the status of C*. And even if C* has been superseded in Australia by C4a and C4b, that still does not rule out a connection between India and Australia, it just makes it more difficult to prove.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)