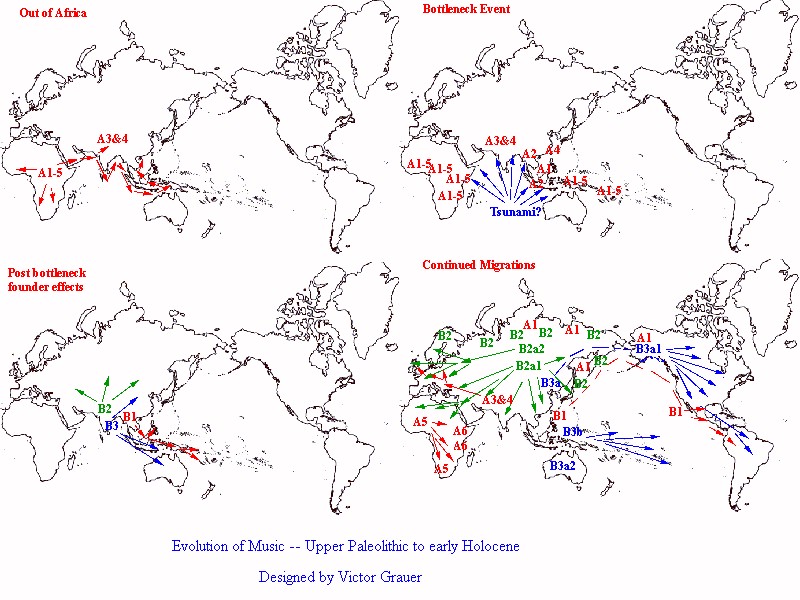

The scenario I've presented in the last few posts is based on an attempt to co-ordinate Stephen Oppenheimer's interpretation of the genetic evidence, including his Toba bottleneck theory, with what I've learned of the musical evidence, and what I am learning about the overall ethnographic picture. I call it an exploration because as I write I am considering other possibilities, exploring the various options for evaluating and interpreting each, and measuring all this against the original hypothesis.

So what has been learned from the exploration so far, and what other options might we consider as we attempt to relate various possibilities to the evidence? And I suppose the answer would be that the possibilities that emerge depend to a large extent on the sort of problems that come to mind. If you see no problem with a straightforward functionalist/diffusionist explanation for the cultural, morphological and genetic similarities and differences we now see in the world around us, and are content to accept independent invention as the best explanation for all the many widespread but isolated similarities not easily attributable to diffusion, then there is no problem with the most straightforward Out of Africa scenario: a small group of humans migrated from Africa to Asia; their descendants expanded along the southern coast of that continent, settling at first in India, where they quickly expanded throughout all of South Asia, with some continuing on to Southeast Asia and eventually migrating from there to East Asia, Siberia and Central Asia, with one or more of the Western colonies branching out to Europe at some point.

The many differences we now see in the world around us would therefore be due to the various adaptations people made to the different environments in which they found themselves; and the similarities would be due to the ways in which certain cultural elements diffused over time from one group to another -- or else to the workings of "convergent evolution," where by virtue of some inborn, universal process that can't really be explained different groups in different places find themselves evolving in a similar direction.

This is one way of thinking about the Out of Africa model, and about anthropology generally, and if one is not overly critical it might seem the most likely and/or reasonable scenario. Whatever problems it might encounter can be attributed to our lack of detailed information regarding exactly how certain features get diffused from one group to another to facilitate change, or how certain practices can be explained as cost-effective adaptations to environmental pressures, or how various encounters and interactions among various neighboring groups can produce, via some sort of genetic and/or cultural "drift," large geographical regions that differ from one another, morphologically, genetically and culturally. This all fits quite nicely with anthropology as currently practiced, where almost all the effort is concentrated on sifting through the myriad details required to explain all the many mini-problems that will invariably emerge from such a vaguely defined model.

This very "reasonable" approach to human evolution breaks down when we see certain problems that become evident only when we do something very few anthropologists of today seem willing to do: carefully and critically examine the patterns that emerge when we consider the large-scale distribution of cultural practices worldwide. The current mainstream approach is a bit like the old Ptolemaic theory of the universe, where the Earth was at the center and all the heavenly bodies revolved around it according to "epicycles" that could only be determined through painstaking and detailed observation and calculation, not at all unlike the laborious efforts of all the armies of anthropologists, archaeologists, paleontologists, etc. seeking to make sense of the human world by either counting and classifying every single stone, bone and sherd or interviewing every "native" in sight.

What convinced me that there is something very wrong with this picture was my discovery, thanks to Alan Lomax, of the remarkably consistent large-scale patterns we become aware of as we systematically study the various musical practices of traditional cultures on a worldwide basis. And once that door is opened, then a magnificent socio-cultural vista becomes discernible, rich with many other possibilities -- and problems.

So. To respond to some comments posted here, accusing me of failing to consider alternatives to the hypothesis I've been exploring, my answer is that I have in fact considered the alternative described above, which is in fact the mainstream interpretation of human evolution generally accepted, in one form or other, by almost all anthropologists, and have been forced to reject it, precisely because it fails to account for certain key pieces of evidence that become apparent only when considering the big picture.

What does this big picture tell us? The answers to that question can be found all over this blog, so there is no need for me to go into all that all over again. But the chief thing on my mind when considering the problem of the later migrations, the key piece of evidence that hits me especially hard as a musicologist, has to do with the distribution of a particular, highly distinctive, musical style, and its various substyles -- namely, what Lomax once called "elaborate style," a type of solo singing characterized by elaborate embellishment; wordiness; complex, "through-composed" forms, often built around various combinations of "mosaic" elements; narrow intervals; frequent use of microtones and other types of vocal nuance; improvisation; tense, constricted vocal timbre; precise enunciation of consonants; accompanied by instruments playing variants of the same melodic line in a manner technically called "heterophony." This is a style of music-making commonly found throughout Asia, from the Middle East (including North Africa) to India to East Asia, Southeast Asia, Island Southeast Asia, and, in a somewhat less extreme form, in Central Asia as well.

As I see it, first of all, it's all but impossible to account for such a style on the basis of a gradual evolution from P/B or any other typically African type of music making. So, unless we are willing to accept the multiregional model, which goes against just about all the genetic evidence, we are, as far as I can see, forced to accept that this is a style that could only have emerged as the result of some sudden, and indeed radical, change. And secondly, the extremely wide distribution of the style, not only among the "high cultures" of Asia and North Africa, but also in so much of the "folk" and even indigenous music as well, combined with the almost total absence of any form of vocal polyphony anywhere in the whole of Asia (with the exception of the many widely scattered, marginalized and isolated groups I've already mentioned), we are drawn almost inevitably to the conclusion that both the absence of polyphony and the presence of this totally different musical style must be due to some dramatic event that could have had such widespread consequences only if it had occurred somewhere in Asia, at some very early period of human history.

[Added 9:54 PM: Sorry, but I forgot to consider Asiatic Russia, which does indeed have some remarkable polyphonic vocal traditions, though Russian folk polyphony seems more closely related to somewhat similar traditions in Europe and also Georgia (which is itself on the cusp between Europe and Asia) than to anything elsewhere in Asia. While true Russian folk polyphony is widespread, both in Europe and Asia, it appears to also be a marginalized survival, largely confined to forest or highland refuge areas.]

So what I am exploring is the various pieces of evidence that have emerged over the last 20 years or so, largely from the field of genetics, to see whether that evidence is consistent with what we see in the musical evidence. And so far I have to say that at least some of this evidence does support the hypothesis I've been considering. But certainly not all. And there are still some very interesting problems that remain.